The PhenX Toolkit: Recommended Measurement Protocols for Social Determinants of Health Research

Cataia L. Ives, Cataia L. Ives, Michelle C. Krzyzanowski, Michelle C. Krzyzanowski, Vanessa J. Marshall, Vanessa J. Marshall, Keith Norris, Keith Norris, Myles Cockburn, Myles Cockburn, Keisha Bentley-Edwards, Keisha Bentley-Edwards, Dinushika Mohottige, Dinushika Mohottige, Keshia M. Pollack Porter, Keshia M. Pollack Porter, Denise Dillard, Yochai Eisenberg, Monik C. Jiménez, Eliseo J. Pérez-Stable, Nancy L. Jones, Jyoti Dayal, Deborah R. Maiese, David Williams, Tabitha P. Hendershot, Carol M. Hamilton

Abstract

Health disparities are driven by unequal conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age, commonly termed the Social Determinants of Health (SDoH). The availability of recommended measurement protocols for SDoH will enable investigators to consistently collect data for SDoH constructs. The PhenX (consensus measures for Phenotypes and eXposures) Toolkit is a web-based catalog of recommended measurement protocols for use in research studies with human participants. Using standard protocols from the PhenX Toolkit makes it easier to compare and combine studies, potentially increasing the impact of individual studies, and aids in comparability across literature. In 2018, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities provided support for an initial expert Working Group to identify and recommend established SDoH protocols for inclusion in the PhenX Toolkit. In 2022, a second expert Working Group was convened to build on the work of the first SDoH Working Group and address gaps in the SDoH Toolkit Collections. The SDoH Collections consist of a Core Collection and Individual and Structural Specialty Collections. This article describes a Basic Protocol for using the PhenX Toolkit to select and implement SDoH measurement protocols for use in research studies. © 2024 The Authors. Current Protocols published by Wiley Periodicals LLC. This article has been contributed to by U.S. Government employees and their work is in the public domain in the USA.

Basic Protocol : Using the PhenX Toolkit to select and implement SDoH protocols

INTRODUCTION

Implications/Relevance

Despite the many advances in biomedical technology and health care delivery, the United States suffers from major disparities in both the delivery and quality of care (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2019) and health outcomes for racial and ethnic minority populations (Liao et al., 2011; Smedley et al., 2003). Health disparities were linked to the unequal distribution of structural or social factors (e.g., economic, sanitation, education) in the United States as early as the 1800s (Beech et al., 2021). Social determinants of health (SDoH) refer to the societal conditions in which individuals are born, grow, live, work, and age (World Health Organization, n.d., as cited in Hill-Briggs & Fitzpatrick, 2023). SDoH are major contributors to health disparities for racial and ethnic minority populations and have become a priority for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Hacker et al., 2022).

Reducing and ultimately eliminating health disparities will require a major focus on identifying, measuring, and assessing interventions for adverse SDoH and their impact on individual and population health outcomes. Having standardized approaches to collecting data needed to assess the impact of SDoH and related interventions is critical. The recent scientific consensus is that race and ethnicity are socio-political constructs. While SDoH can yield important insights into the community- or societal-level factors that impact health, it is equally important to recognize that the causal pathway to structural inequities may differ across racial and ethnic groups. For instance, while there may be a similar community-level socioeconomic status for various groups, the laws, policies, and practices that created and now control these structural inequities can significantly impact group-level mobility (Nazroo, 2003; Williams, 1999).

SDoH have been shown to influence a range of health outcomes; for example, poverty is highly correlated with poorer health outcomes (CDC, 2022). Because SDoH have a significant impact on a variety of health outcomes, it is crucial for the research community to define and adopt SDoH measurement standards (Krzyzanowski et al., 2023). These may vary from environmental exposures (e.g., air quality) that may directly impact biologic and physiologic functioning to access to health care and more. These community- and societal-level exposures, such as environmental toxin exposure, food deserts, housing density, educational quality, minimum wage policy, access to care, and more, may impact the development, progression, and response to treatment of many clinical conditions (CDC, 2023). An individual's exposures may differ over time. Community- and societal-level exposures may be directly impacted by shifting policy landscapes and require the engagement of multisector stakeholders. The availability of validated, standardized protocols can accelerate the research needed at multiple levels to reduce racial and ethnic disparities for many chronic conditions. Individual interactions with structural social determinants may vary substantially based on demographic characteristics and individual social determinants that may affect health outcomes. Thus, standardized measures of demographic factors (e.g., race and ethnicity) and individual social determinants (e.g., food security) are complementary and essential to consistent measurement of structural SDoH.

The PhenX Toolkit

The PhenX (consensus measures for Phenotypes and eXposures) Toolkit (https://www.phenxtoolkit.org) is a web-based catalog of recommended measurement protocols of phenotypes and exposures suitable for inclusion in epidemiological, genomic, clinical, and translational research studies involving human participants (Hamilton et al., 2011). The measurement protocols in the PhenX Toolkit are recommended by expert Working Groups using an established PhenX consensus process (Maiese et al., 2013). Since 2007, PhenX has been funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute with co-funding from other National Institutes of Health (NIH) Institutes, Centers, and programs. Use of measurement protocols from the PhenX Toolkit provides a standard, consistent approach for collecting data, such as by self-report or interviewer-administered questionnaires, physical measurements, and bioassays, or for performing secondary data analysis from available datasets (e.g., U.S. Census). A list of PhenX terms and definitions is provided in Table 1.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Core collection | A Core Collection includes protocols that are deemed relevant for all studies in a specific topic or field of research to ensure collection of comparable data across studies |

| Specialty collection | A Specialty Collection is complementary to a Core Collection and provides more in-depth assessments of a specific topic or field of research |

| Individual Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) collection | The Individual SDoH Specialty Collection includes measurement protocols for use in research where information is being collected from and about people answering for themselves at the individual level about their physical/built and sociocultural environment or health care system |

| Structural Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) collection | The Structural SDoH Specialty Collection includes measurement protocols at the societal or community level measuring the physical/built environment or sociocultural environment of a specific geographic area, such as state or county or a census-defined unit, e.g., census tract or ZIP code |

| Measure | A standard way of capturing data on a certain characteristic of, or relating to, a study subject |

| Protocol | A standard data collection procedure, or measurement protocol, recommended by a PhenX Working Group |

| Scope element | A topic critical to the domain or collection proposed by the funding agency and its Working Group |

| Essential protocol | PhenX protocols that generate data required to accurately interpret the results of another protocol |

| Related protocol | Protocols that are conceptually related and curated by the Working Group members |

- a Source: PhenX Toolkit, https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/help/glossary; https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/resources/phenx/

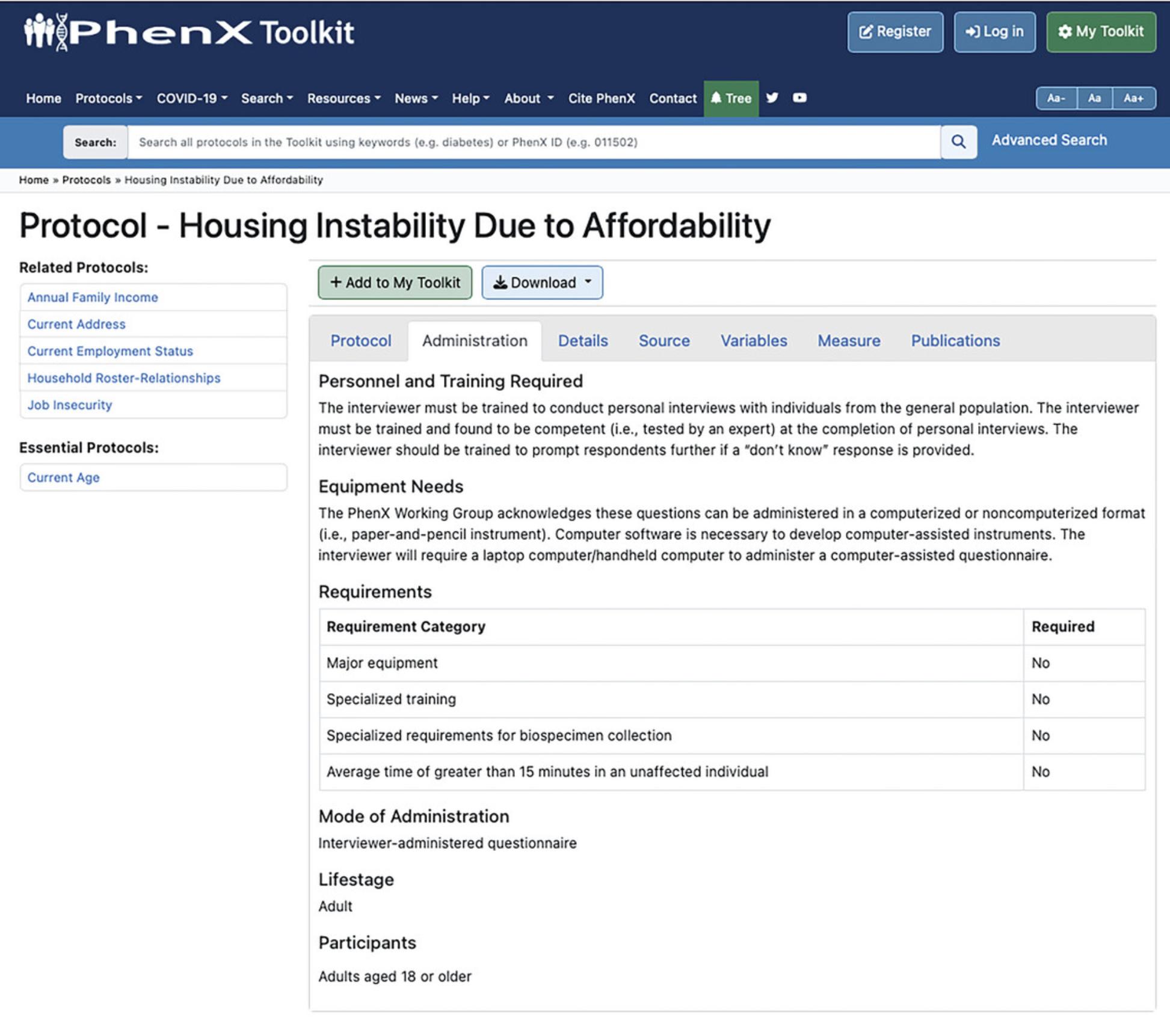

The PhenX Steering Committee (SC) provides overarching guidance to the PhenX project. The SC defined the criteria for selecting protocols to be included in the Toolkit, including that they are clearly defined, well-established, broadly applicable, and broadly validated with demonstrated utility, with a preference for those that are publicly available (Hamilton et al., 2011). In addition, protocols are evaluated for burden in terms of the use of major equipment, need for specialized training, specialized requirements for biospecimen collection, or an average time of >15 min in an unaffected individual. In the Toolkit, these characteristics, annotated Yes/No, are detailed on the “Administration” tab in the Requirements Table of the protocol (Fig. 1).

Background of the PhenX SDoH Project

The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) Research Framework (NIMHD, 2017; Pérez-Stable & Collins, 2019) is a multidimensional model to facilitate assessment of progress and opportunities in minority health and health disparities research. It includes a wide range of health determinants, organized as domains of influence across multiple areas, from the physical/built environment to the health care system, and levels of influence, including individual, interpersonal, community, and societal. In keeping with the Framework to recognize the importance of factors beyond the individual level and to encourage a cultural shift toward using recommended, standard measures for SDoH, in 2018, NIMHD turned to PhenX to identify a consensus set of measurement protocols on SDoH using the established PhenX consensus process.

In 2018, the first expert Working Group was convened to identify and select well-established, broadly applicable SDoH measurement protocols and make them publicly available in the PhenX Toolkit. Their work was guided by an initial scope developed by NIMHD and the NIH-wide SDoH PhenX Toolkit workgroup. In 2020, their work resulted in the creation of PhenX SDoH Collections of protocols, including a Core Collection intended for use in all research studies and Individual and Structural SDoH Collections (Krzyzanowski et al., 2023). Following this effort, the NIH-wide SDoH PhenX Toolkit workgroup identified additional priority topic areas of SDoH for which standard measures would be useful. In 2022, NIMHD funded an expansion of the PhenX SDoH collection, and a second expert Working Group was assembled to address these topic areas. This paper discusses the activities and results from the second Working Group.

The PhenX SDoH Collections (https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/collections/view/6) consist of the Core Collection, Individual Specialty Collection, and Structural Specialty Collection (Table 1). The two Specialty Collections are complementary to the Core Collection and support more nuanced investigations of how SDoH influences health. The collections include protocols identified by both PhenX SDoH Working Groups, as well as previously established PhenX protocols in the Toolkit, such as Annual Family Income and Discrimination. The PhenX Toolkit recommends the SDoH Core Collection for use by all Toolkit users, as it provides a common currency for all investigators conducting research with human participants. Additionally, NIMHD strongly encourages using measurement protocols from the PhenX SDoH Core and Specialty Collections (NIH Office of Extramural Research, 2020). The PhenX SC recommends using the SDoH Core Collection for COVID-19 research (Krzyzanowski et al., 2021). The PhenX COVID-19 Research Collections and the PhenX Sickle Cell Disease Psychosocial and Social Determinants of Health Collection include the SDoH Core Collection as a recommended collection for research.

The Basic Protocol outlined in this article provides step-by-step guidance for using the PhenX Toolkit to identify standard SDoH protocols in the PhenX Toolkit for study design and using PhenX Toolkit features to effectively implement the protocols. The Basic Protocol outlines how to navigate, browse, and save and download protocols from the PhenX Toolkit for inclusion in a research study.

STRATEGIC PLANNING

SDoH Working Group Process

The NIH-wide SDoH PhenX Toolkit workgroup recommended expanding the existing SDoH Collections, including adding both existing PhenX protocols and new protocols not yet in the PhenX Toolkit. Considering the recommendations from the NIH-wide SDoH PhenX Toolkit workgroup, NIMHD developed an initial scope (Table 2) of elements that provided a framework for the protocols the SDoH Working Group would consider for inclusion in the Toolkit.

| 1. Built and natural environments |

| 2. Structural racism/hierarchy/discrimination |

| 3. Economic resources |

| 4. Health and health care |

| 5. Sociocultural community context |

To address the SDoH scope elements, eight experts with research experience in discrimination, racism, access to health care, disability and religiosity, and general health disparities research, were recruited to serve. The SDoH Working Group was responsible for identifying measurement protocols to complement the SDoH protocols that were already in the Toolkit.

The Working Group met by teleconference in February and March 2022. Using the scope elements as a framework, the Working Group aimed to identify specific measurement protocols to address each of the scope elements, especially those elements without existing protocols in the Toolkit. In their discussions, the Working Group considered, but did not include, some concepts that did not fit in the framework of the Built Environment scope element, such as the exposome. The Working Group did not address scope elements that were already covered by the first SDoH Working Group, including Employment Status, Occupational Health & Safety, Education, Environmental Exposures, and Food Environment. In their review of literature, the Working Group identified important areas where protocols that met the PhenX selection criteria of being well-established and broadly validated could not be identified. These areas for future research are discussed more in the Limitations section (see Commentary).

During their discussions, the Working Group identified considerations that impacted their consensus building and decision-making. One consideration was that some questions may work well with specific populations but not for the general population. Another consideration in selecting protocols was their availability in languages other than English, especially Spanish, as translations make the protocol more broadly accessible for diverse patient populations and marginalized communities. In their recommendation of protocols for each scope element, the Working Group preferred protocols available in multiple languages over protocols for which a translation was not available.

The Working Group identified 14 preliminary protocols to share with the broader scientific community to get feedback. An email outreach was sent to PhenX and NIMHD listservs, giving the community the opportunity to provide feedback on the protocols proposed by the Working Group. Because they had difficulty finding a publicly available protocol for Accommodations for Mental/Physical Disability, the Working Group asked the community for recommendations.

PhenX received 95 responses to the community outreach. The responses indicated widespread support for the Working Group recommendations. In September 2022, a final meeting was held to discuss the feedback from community outreach and finalize the protocols for inclusion in the Toolkit. Feedback regarding the Healthcare Communications protocol asked the Working Group to consider adding Health Literacy and English Proficiency as Essential Protocols. Essential Protocols are deemed necessary to accurately interpret the results of a specific protocol, in this case, Healthcare Communications. The Working Group decided to add Health Literacy as a Related Protocol to Healthcare Communications, meaning that it is conceptually related to the Healthcare Communications protocol and its use is suggested. Although there was an existing Health Literacy protocol in the Toolkit, the Working Group looked for, but did not identify, a protocol that was easier to administer. The Working Group discussed the feedback received about health literacy, such as assessment at reading levels, as a cross-cutting concern for SDoH and a topic for future research.

Feedback received during outreach included several recommendations for protocols. For example, for Minimum Wage, the community suggested that living wage was more valuable than minimum wage to collect; however, the Working Group noted the lack of standardized measures for living wage. Feedback regarding Religious Behaviors and Congregational Support indicated a need for a validated, nondenominational protocol. As a result, the Working Group identified a nondenominational version of the protocol for inclusion in the Toolkit.

Results

The Working Group recommended 15 protocols for inclusion in the PhenX Toolkit. One of the protocols addressing health care access was split to measure Affordability Problems in Accessing Dental Care and Affordability Problems in Accessing Prescriptions. Ultimately, the Working Group identified the following protocols that met the Toolkit requirements: Affordability Problems in Accessing Dental Care, Affordability Problems in Accessing Prescriptions, Discrimination in Health Care, Family History of Incarceration, Healthcare Communications, Housing Instability Due to Affordability, Internet Access, Minimum Wage, Neighborhood Walking and Biking Environment, Perceptions of Housing Insecurity, Physical Activity – Neighborhood Environment, Racial/Ethnic Discrimination – Recent and Lifetime, Religious Behaviors and Congregational Support, Residential Concentrations of Income, and Water Access and Sanitation. As a result, in December 2022, all 15 protocols were approved for inclusion by the PhenX SC and released in the Toolkit (Table 3). In 2022, the PhenX SC recommended that the protocols in the SDoH Core Collection be included in all studies with human participants.

| Specialty collection | Protocol | Protocol source |

|---|---|---|

| Individual SDoH collectionb | Affordability Problems in Accessing Dental Care | Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component (MEPS-HC) |

| Affordability Problems in Accessing Prescriptions | Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component (MEPS-HC) | |

| Discrimination in Health Care | Discrimination in Medical Settings (DMS) scale | |

| Family History of Incarceration | Family History of Incarceration Survey (FamHIS) | |

| Healthcare Communications | Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Adult Self-Administered Questionnaire (SAQ) | |

| Housing Instability Due to Affordability | CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Survey | |

| Internet Access | Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) | |

| Perceptions of Housing Insecurity | The Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Health-Related Social Needs (HRSN) Screening Tool | |

| Physical Activity – Neighborhood Environment | Physical Activity Neighborhood Environment Survey (PANES) | |

| Racial/Ethnic Discrimination – Recent and Lifetime | The General Ethnic Discrimination (GED) Scale | |

| Religious Behaviors and Congregational Support | Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality (BMMRS) | |

| Structural SDoH Collectionc | Minimum Wage | U.S. Department of Labor, State Minimum Wage Laws, 2022 |

| Neighborhood Walking and Biking Environment | Microscale Audit of Pedestrian Streetscapes (MAPS-Mini) | |

| Residential Concentrations of Income | Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE) | |

| Water Access and Sanitation | American Housing Survey (AHS), 2019 |

- a Source: https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/resources/phenx/

- b Information collected from and about people answering for themselves at the individual level about their physical/built and sociocultural environment or health care system.

- c Protocols at the societal or community level measuring the physical/built environment or sociocultural environment of a specific geographic area, such as a state or county or a census-defined unit, e.g., a census track or ZIP Code.

The Working Group added Internet Access addressing type of Internet service and how the Internet is accessed using the Health Information National Trends Survey, a topic that rose in prominence when many students attended school from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. For Walkability, the Working Group recommended two protocols: Neighborhood Walking and Biking Environment, from the Microscale Audit of Pedestrian Streetscapes covering neighborhood infrastructure within a 0.25-mile walking path, and Physical Activity – Neighborhood Environment, from the Physical Activity Neighborhood Environment Survey covering transportation infrastructure and nearby amenities. To address water access, the Working Group added American Housing Survey questions on Water Access and Sanitation. The COVID-19 pandemic also exposed the need for housing relief as people lost their jobs, and its impact on health and stress levels prompted the addition of Housing Instability Due to Affordability and Perceptions of Housing Insecurity. Minimum Wage was added to provide information on state minimum wages and their change over time. Affordability Problems in Accessing Dental Care and Affordability Problems in Accessing Prescriptions addressed concerns in accessing oral health care and the ability to pay for it. The Healthcare Communications protocol from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey assesses effective communications with health professionals during a health care visit. To address discrimination and structural racism, the Working Group added Residential Concentrations of Income, which can result from structurally racist housing and lending policies (Larrabee Sonderlund et al., 2022), and Discrimination in Health Care and Racial/Ethnic Discrimination – Recent and Lifetime, which address lived experiences in discrimination. The Working Group added Family History of Incarceration describing prevalence of incarceration for family members. They added Religious Behaviors and Congregational Support, assessing multiple aspects of religiousness and spirituality, to fill in the final measurement protocols.

The protocols added to the SDoH Individual and Structural Specialty Collections provide researchers with options to conduct assessments on specific SDoH topics. Protocols may be selected from the Specialty Collections as needed for an investigator's study design and research needs. Individual protocols and their sources are listed in Table 3. Eleven protocols added to the Individual SDoH Specialty Collection collect data from individual respondents and come from international, federal, and state surveys. Individual-level data may be aggregated to reflect the population of interest.

Four structural protocols include societal- or community-level assessments for specific geographic areas, such as states, counties, metropolitan areas, or census tracts using secondary data from well-established government sources, e.g., the U.S. Census, the American Community Survey, and the Environmental Protection Agency. Four protocols were added to the Structural SDoH Specialty Collection. The SDoH Working Group did not add any high-burden protocols to the Toolkit. Of the 15 protocols added to the Toolkit by the SDoH Working Group, six are available in Spanish.

Basic Protocol: USING THE PhenX TOOLKIT TO SELECT AND IMPLEMENT SDoH PROTOCOLS

Provided are step-by-step instructions for selecting SDoH protocols in the PhenX Toolkit to contribute to a new study design or expand an existing study. The example is that of an investigator designing a new research study and planning to include SDoH measures. The investigator will assess a variety of phenotypes and exposures for a cohort with diverse participants. The researcher is interested in learning more about the participants’ access to stable and affordable housing and their perceptions about their housing situation. The study will collect basic demographic information about participants.

The researcher recognizes the use of standard, high-quality, well-established protocols to facilitate reproducibility and downstream cross-study analysis. They want to know which recommended SDoH measurement protocols from the PhenX Toolkit will be useful for inclusion in their study. The investigator follows these steps to identify recommended SDoH-related protocols from the Toolkit.

Materials

- Computer or laptop

- Internet browser

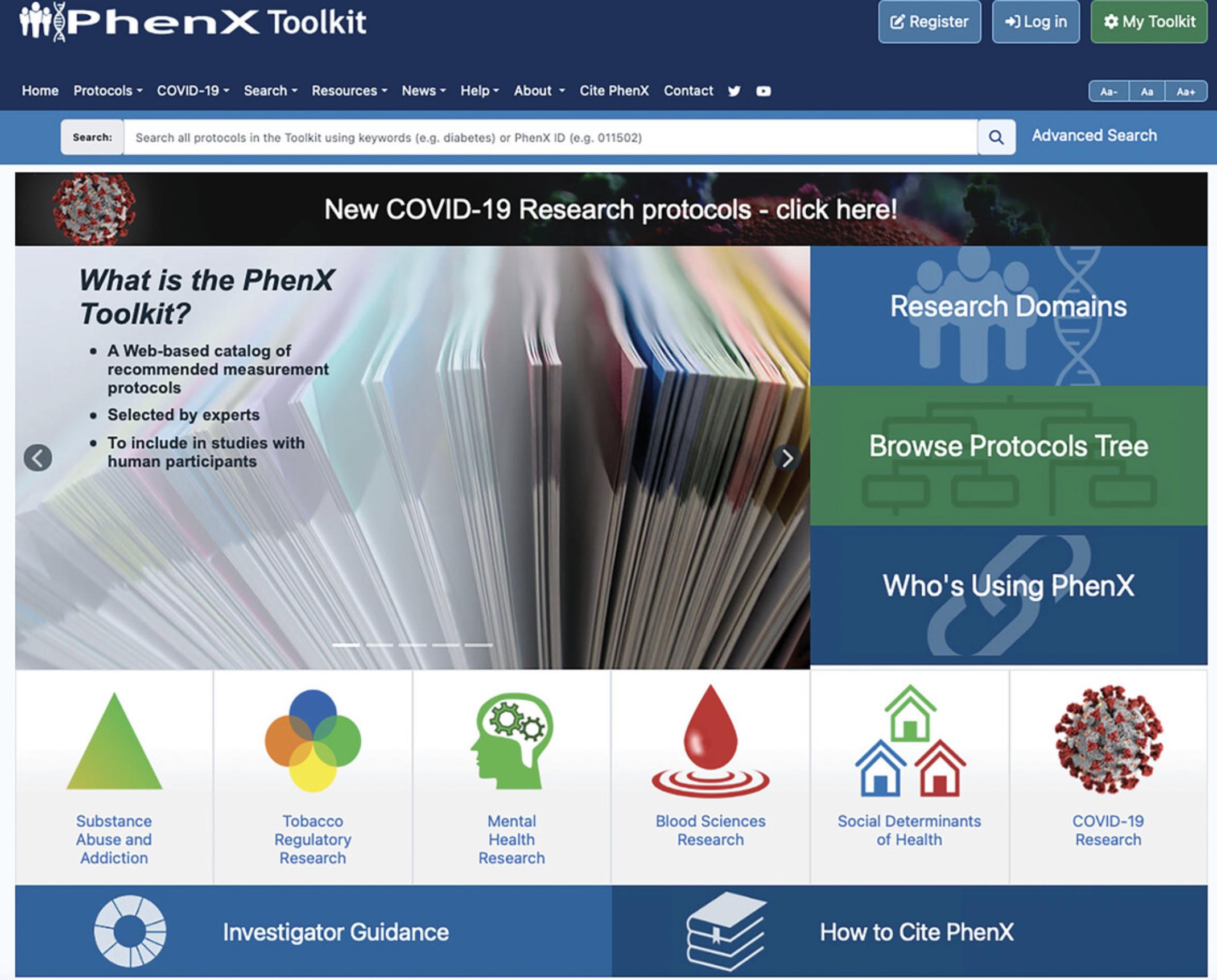

1.Navigate to https://www.phenxtoolkit.org. The SDoH Collections can be reached by clicking the “Social Determinants of Health” button on the homepage (Fig. 2).

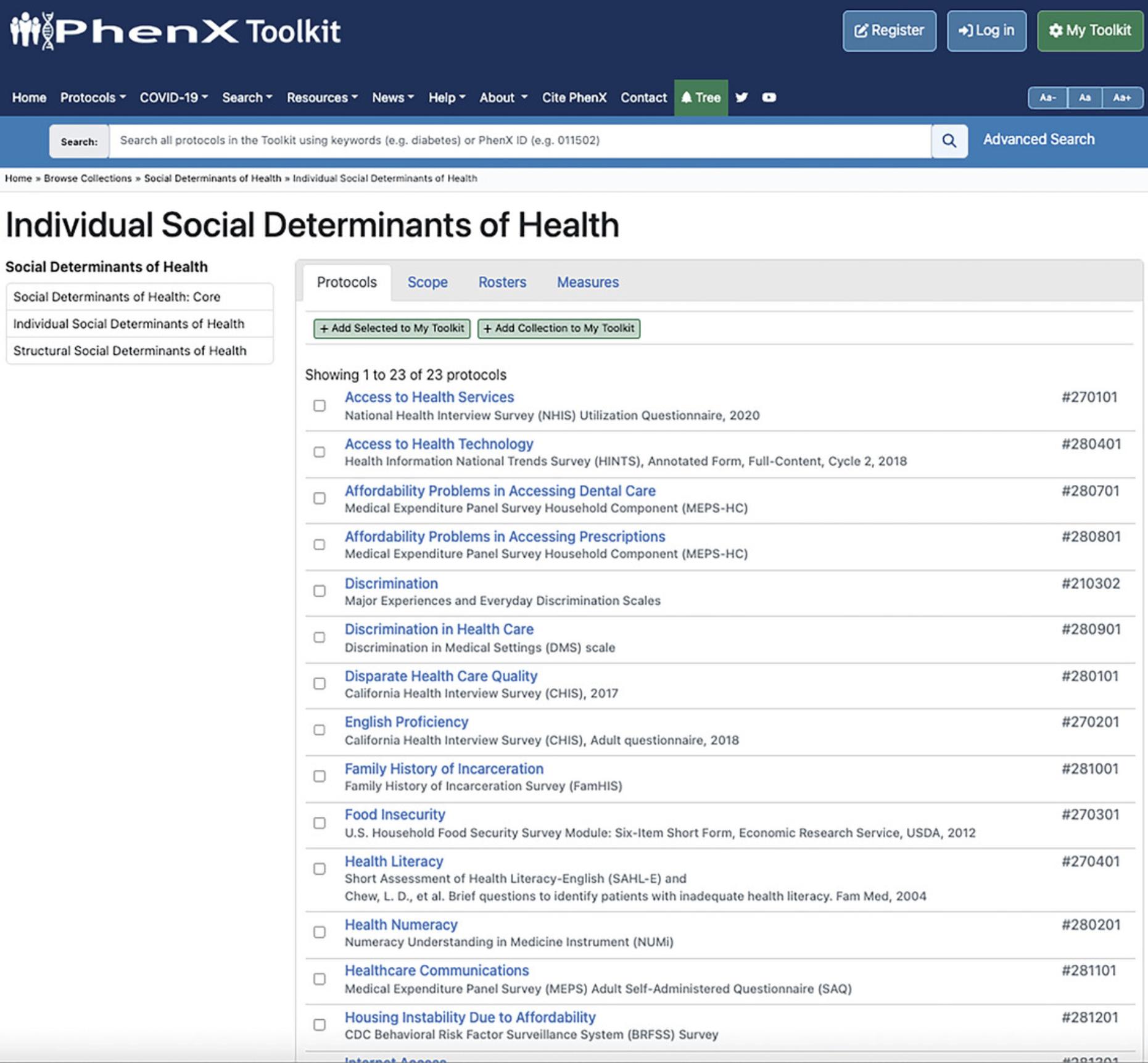

2.Browse protocols in the SDoH Collections (Fig. 3).

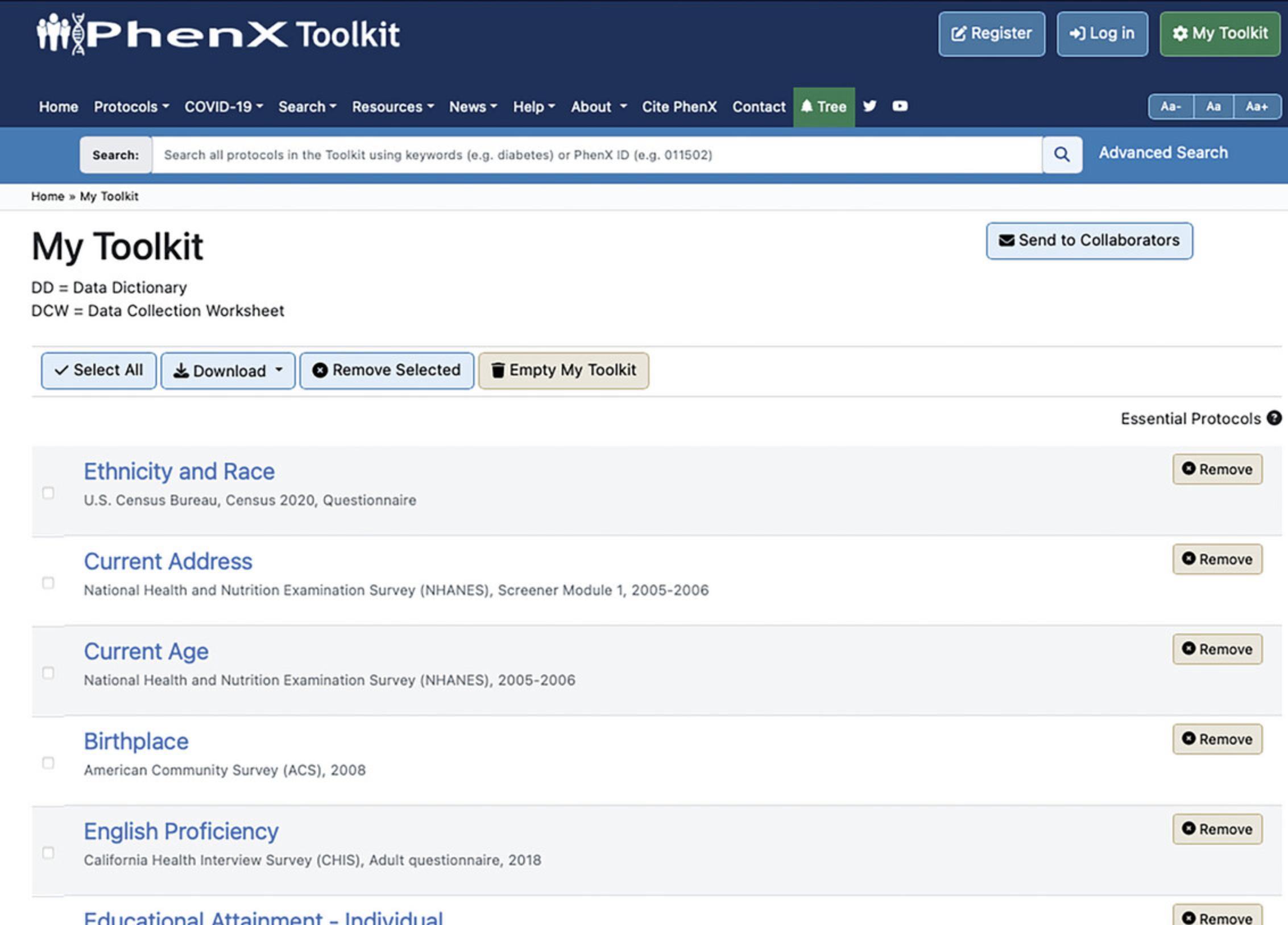

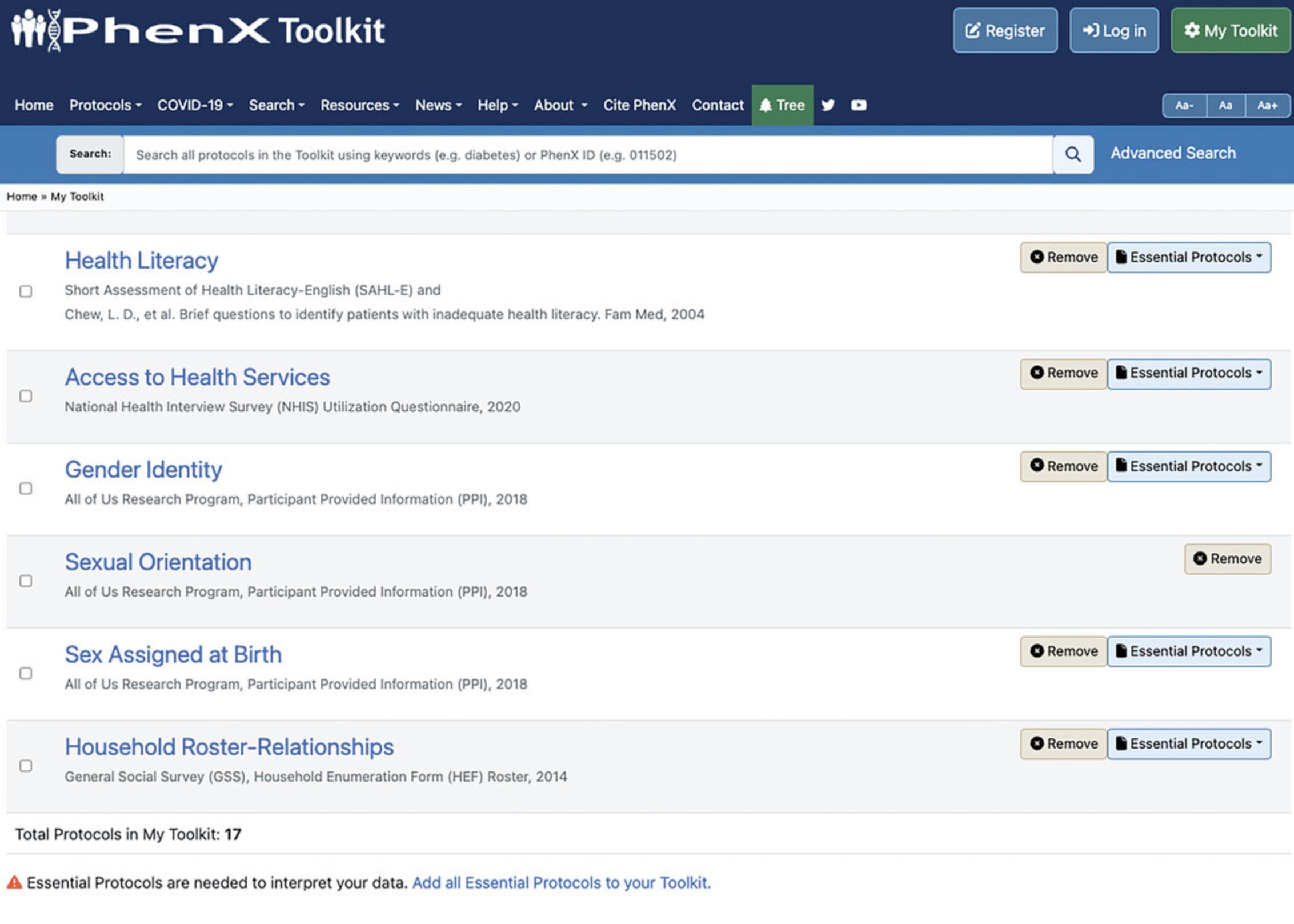

3.Add the entire Social Determinants of Health: Core Collection to your Toolkit via “Add to My Toolkit.” This will display the contents of the Toolkit, analogous to an online shopping cart, with selected protocols being saved there (Fig. 4).

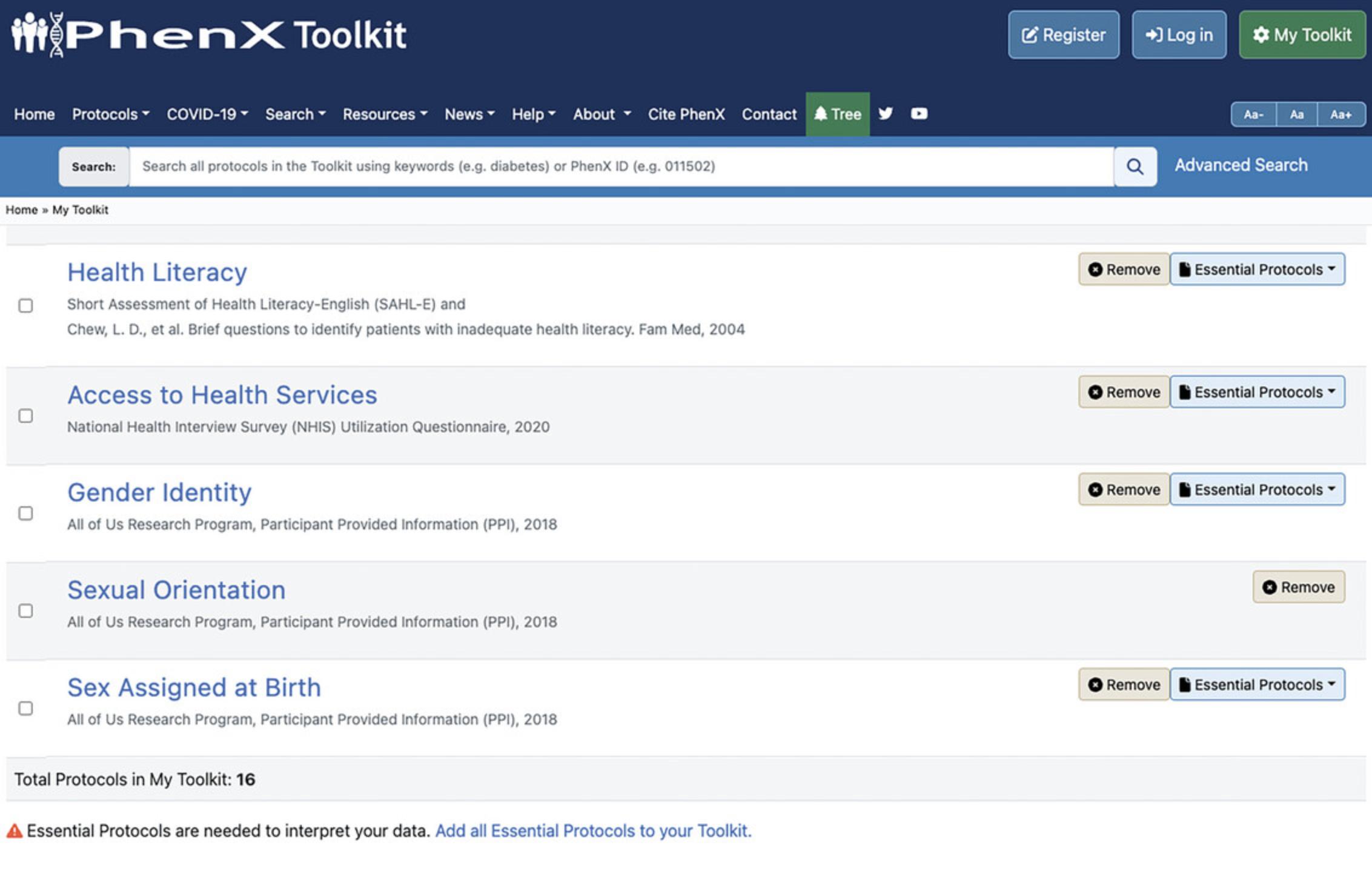

4.Scroll to the bottom of the page and select “Add all Essential Protocols to your Toolkit” (Fig. 5).

5.Browse the Individual SDoH Collection (Fig. 7).

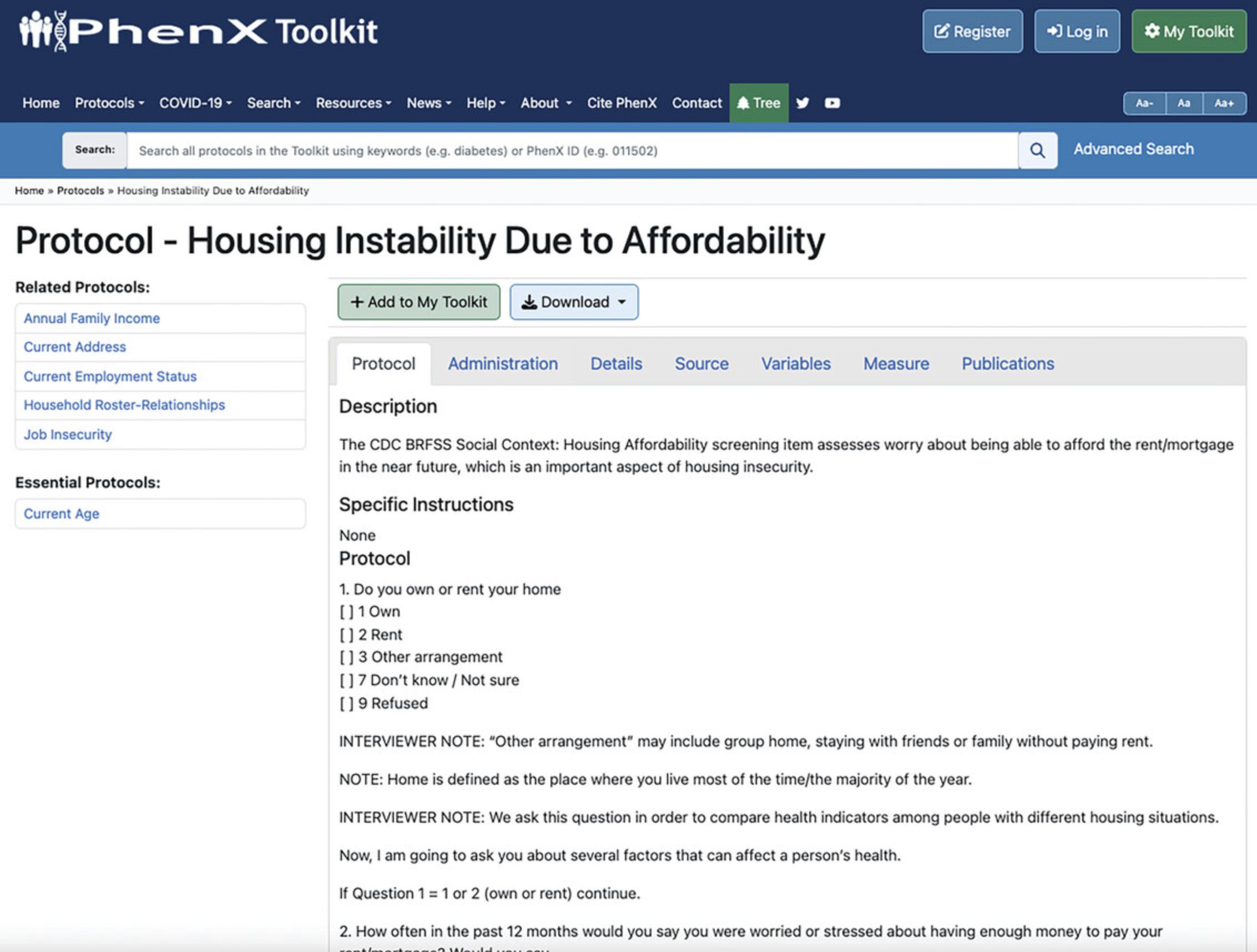

6.Clicking the protocol name allows you to view additional details for each, like a description of the protocol (Fig. 8), specific instructions for administration, and related protocols. Select the Housing Instability Due to Affordability and Perceptions of Housing Insecurity protocols and add them to your Toolkit via “Add to My Toolkit.”

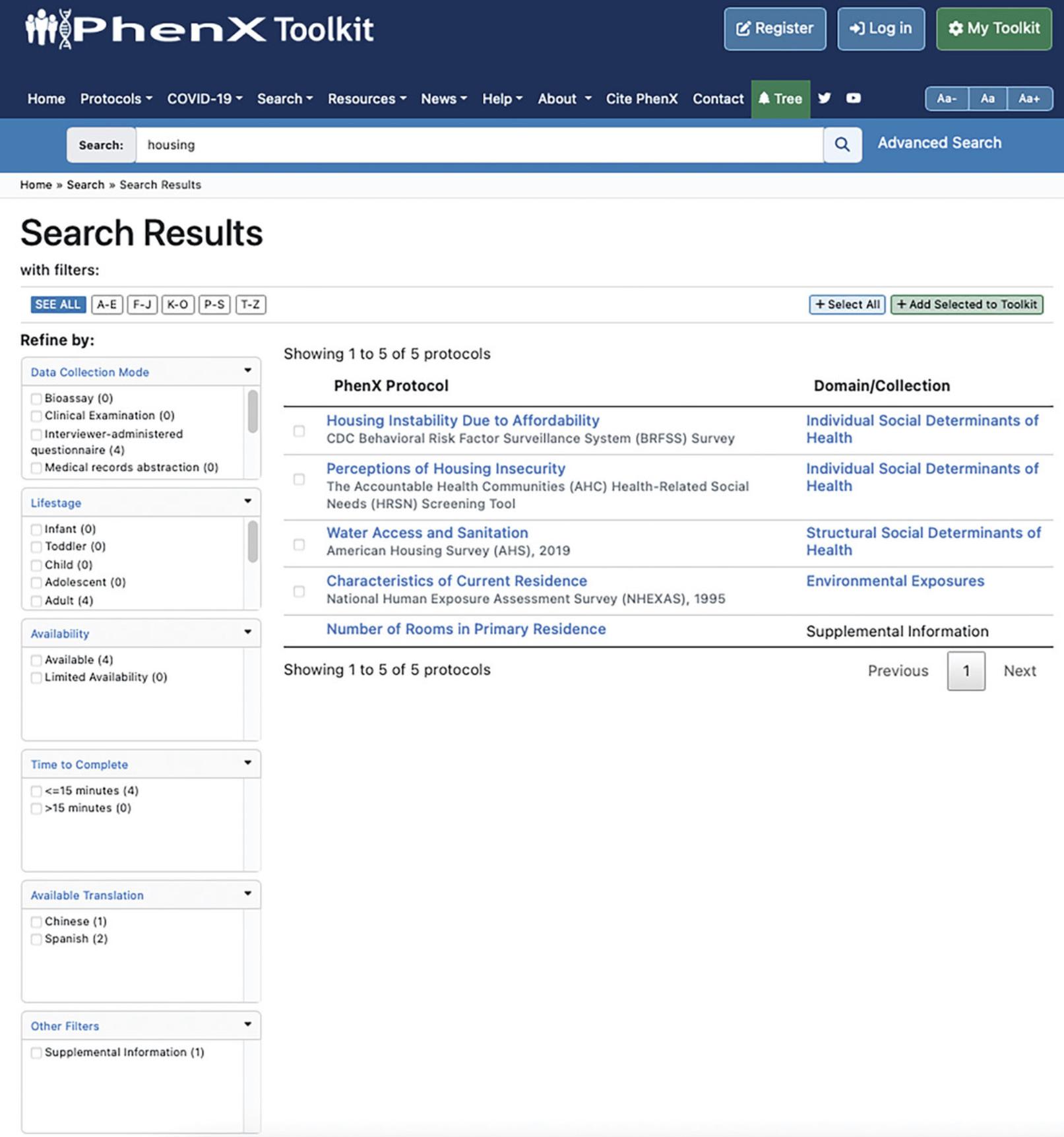

7.Search the entire Toolkit for additional measurement protocols relevant to the study design (Fig. 9).

8.Once all protocols have been added to My Toolkit, click “Select All” or individually select protocols to highlight protocols of interest.

9.By selecting “Download,” investigators can choose to download a basic report, a detailed report, a Data Collection Worksheet (multiple language options), or a Data Dictionary (multiple formats).

-

Basic Reports include a listing of all the protocols in My Toolkit and the Essential Protocols associated with them. For each protocol, they list protocol ID, protocol description, specific instructions, and the protocol text.

-

Detailed reports include a listing of all the protocols in My Toolkit and the Essential Protocols associated with them. For each protocol, they list protocol ID, protocol description, specific instructions, protocol text, selection rationale, language, participants, personnel, and training required to perform the protocol, equipment needs, standards, references, protocol type, derived variables, and requirements.

-

Data Collection Worksheet(s) include questions to collect information from research participants. If the protocol has been translated into a language other than English, other language options may be available for download.

-

Data Dictionaries provide definitions of variables and other relevant parameters for a study's data management system. They also provide detailed information about each variable as well as skip patterns that are implemented throughout. Downloading in REDCap format allows investigators to upload directly to a REDCap data collection instance. The CSV format is compatible with data submission to the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes.

COMMENTARY

Background Information

Using high-quality, well-established, standard protocols from the PhenX Toolkit makes it easier to compare and combine data across studies and allows for comparison of study data, particularly when findings require validation. Combining results can result in increased sample size providing greater statistical power in downstream analyses (Cox et al., 2021). Cross-study analyses potentially increase the impact of individual studies over time (Hamilton et al., 2011). Increased emphasis on adhering to Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) principles and data sharing has increased the utility of standard measures or common data elements for research (Wilkinson et al., 2016). Standard protocols for the measurement of SDoH play a crucial role in health disparities research, as they provide a structured framework for assessing the impact of different elements of social support across health outcomes and across communities (Krzyzanowski et al., 2023). By following these SDoH protocols, researchers of health disparities can minimize bias, facilitate replication and validation of research studies, and improve the sharing and synthesis of research findings across studies, which is essential for improving health outcomes. This will lead to a better overall understanding of the impact of SDoH on individual- and population-level health outcomes and better inform the interventions and policies needed to improve health outcomes and reduce health disparities. Overall, PhenX Toolkit SDoH Collections provide a critical resource for standardizing health disparities research protocols and practices.

Critical Parameters and Troubleshooting

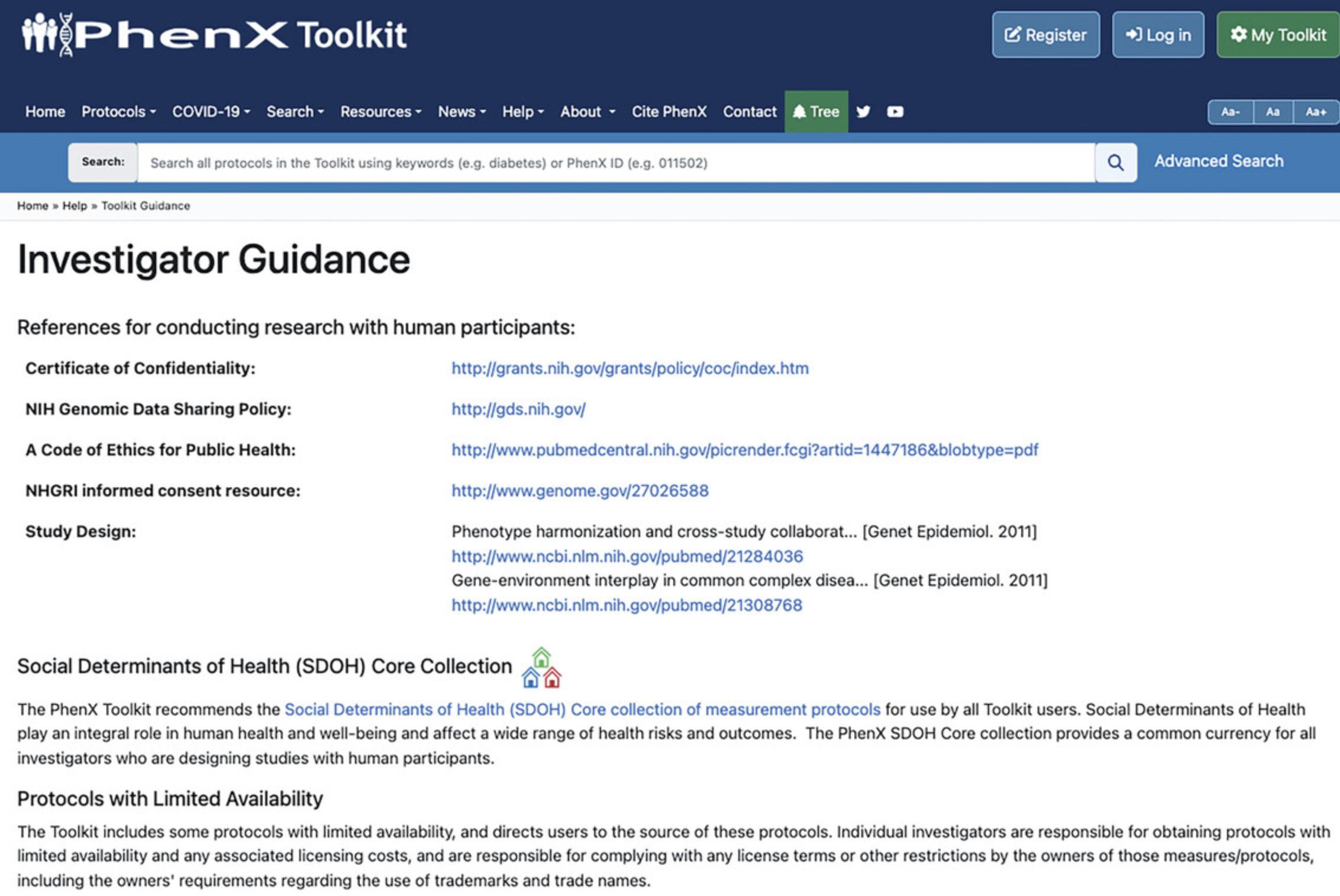

The above Basic Protocol explains how an investigator can identify recommended SDoH-related protocols from the Toolkit for inclusion in their study. In addition to browsing the SDoH Collections and the Toolkit for relevant SDoH protocols, the investigator should consider the Toolkit guidance (https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/help/guidance) recommending use of the SDoH Core Collection for all Toolkit users (Fig. 10). The Core Collection provides a common currency for all investigators designing studies with human participants.

The PhenX Toolkit provides recommendations for Essential Protocols that are necessary to accurately interpret the results of another protocol. For example, if a user selects the Water Access and Sanitation protocol, the Toolkit will also recommend collecting the Current Address, which is essential to assessing water access and sanitation at the household level. The Toolkit provides data management tools to help investigators use protocols in designing studies. PhenX Data Collection Worksheet(s) make it easy to integrate protocols during data collection. Data Dictionaries enhance data sharing and allow for integration into data management systems including REDCap.

Understanding Results

The protocols that the SDoH Working Group added to the PhenX Toolkit address high-priority topic areas as outlined in the NIMHD Research Framework, the recommendations of the NIH-wide SDoH PhenX Toolkit workgroup, and the scope that NIMHD developed for the SDoH Working Group. Furthermore, the final protocols are in alignment with NIH priorities including the following four Minority Health and Health Disparities Strategic Plan Goals: (1) promote research to understand and improve minority health research; (2) advance scientific understanding of the causes of health disparities; (3) develop and test interventions to reduce health disparities; and (4) create and improve scientific methods, metrics, measures, and tools (NIMHD, 2022).

NIH supports related efforts for understanding and promoting health disparities research. For example, The Healthy People 2030 Framework established overarching goals related to achieving health equity in the coming decade (Gómez et al., 2021). The All of Us Research Program launched their SDoH survey in 2021 to collect information about participants’ social and environmental factors in their everyday lives (All of Us Research Program, 2021). Krzyzanowski et al. (2023) included a crosswalk of protocols in the PhenX Toolkit with protocols from the All of Us SDoH survey. In 2023, NIH launched the Community Partnerships to Advance Science for Society Program, a community-led research program to address the underlying structural factors within communities that affect health (NIH Office of Strategic Coordination, 2023). The National COVID Cohort Collaborative, which houses patient-level data derived from electronic health records from many clinical centers on patients with COVID-19, is exploring the impact of SDoH on COVID-19 (Haendel, Chute et al., 2021; Haendel, Housman et al., 2021).

As of July 2023, NIH developed a unified conceptualization of SDoH for NIH-wide coordination and strategic growth of evidence base for advancing SDoH and its impact on research (National Institute of Nursing Research, n.d.; National Institute of Nursing Research, 2023). NIH recognizes the significant investment in SDoH research and invested ∼$4.1 billion in fiscal year 2022, funding >8,300 SDoH research and training programs (National Institutes of Health, Office of Extramural Research, 2023b). Furthermore, most of the NIH Institutes and Centers are encouraging use of the PhenX Toolkit as a resource to employ a common set of tools that will promote the collection of comparable data on SDoH across studies, thereby promoting data harmonization for SDoH (NIH Office of Extramural Research, 2020; National Institutes of Health, Office of Extramural Research, 2023a).

The SDoH Collections were initially presented at the American Society for Human Genetics Annual Meeting in 2022 (Krzyzanowski et al., 2022). News of the release of the Collections was shared via the PhenX and NIMHD distribution lists. As of July 2023, 621 NIH funding opportunity announcements mention or encourage the use of PhenX protocols and linked to the PhenX Toolkit. Of domains and collections in the PhenX Toolkit, the SDoH Collections have consistently been among those most frequently added to My Toolkit by Toolkit users. The SDoH Collections had been added to My Toolkit >44,000 times. Also, the individual protocols from the SDoH Collections have been frequently used. For example, Toolkit users had viewed the SDoH protocols >55,000 times.

Limitations

The SDoH Working Group identified specific, validated protocols to expand on the SDoH protocols already in the PhenX Toolkit. In some instances, they were unable to identify a protocol for the Toolkit, either because the existing protocols did not meet PhenX selection criteria or there was no existing protocol. The Working Group identified these topics as areas for future research and measure development as SDoH continues to expand as a field of research. The Working Group identified but did not find a protocol meeting the PhenX inclusion criteria for health literacy, reasons and challenges in accessing health care information, accommodations for physical and mental disability, policing, and transportation during their discussions. For the topics of religion and spirituality and incarceration, the Working Group added the protocols Religious Behaviors and Congregational Support and Family History of Incarceration to the SDoH Collections but also named these as areas for future research.

The Working Group identified structural racism and discrimination as topics for future research and measurement. Several leading scholars have offered definitions of structural racism including the “totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination through mutually reinforcing systems of housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, and criminal justice” (Bailey et al., 2017). There has been increasing attention to the unique challenges posed in conceptualizing, measuring, and uniformly approaching structural racism in research. The challenges associated with the measure of structural racism relate to its universal, but varied, impact on different health outcomes and the contribution of structural racism to racialized social determinants or drivers of health across multiple domains, which can differ across place and time (Adkins-Jackson et al., 2022; Braveman et al., 2022). Additional research is needed that quantifies the specific elements of the adverse SDoH that drive disparate health outcomes for different conditions. Opportunities to define, measure, and intervene upon structural racism and other structural inequalities will require long-term concerted efforts to identify and shift power dynamics that undergird these structures (Heller et al., 2023). This includes learning from numerous community-led efforts (NIH Office of Strategic Coordination, 2023) to intervene on SDoH through multi-level interventions. Indeed, NIH has recently called for research on structural racism and discrimination, both in etiology and interventions; thus, progress is anticipated on development of measures for structural racism (National Institutes of Health, Office of Extramural Research, 2021; National Institutes of Health, Office of Extramural Research, 2023a). The NIH-wide UNITE initiative funded 38 studies to understand the role of structural racism and discrimination in causing health disparities, for a total budget of $34 million in the first year of the program (National Institutes of Health, Office of Extramural Research, 2021; NIMHD, 2023).

The Working Group also identified discrimination in health care as a topic area for further research. There has been increased attention to the role of bias and discrimination on health outcomes among minoritized individuals (Smedley et al., 2003). Several investigators have described explicit and implicit biases in health care, and others have used well-validated measures to assess racial discrimination in health care, including single-item assessments of discrimination in health care, a multi-item measure of personal experiences of discrimination, measures of general racism in health care, and “perceived” racism in health care (Bird & Bogart, 2001; Hausmann et al., 2010; Krieger et al., 2005; LaVeist et al., 2000). Although increasing efforts have been made to identify the unique ways in which individuals experience discrimination across the life course, the measurement and appropriate capture of intersecting forms of discrimination (e.g., due to gender, sexual orientation) has been challenging due to their compounding nature, and few studies have effectively measured synergistic effects of intersecting forms of discrimination or marginalization on individuals in association with health conditions or access. Novel tools that effectively measure intersectional discrimination across the life course are needed (Howard et al., 2019; Lett et al., 2023; Scheim & Bauer, 2019), and many of these will require input from multiple stakeholders, e.g., individuals impacted by these experiences.

Similarly, religion and spirituality were not already addressed in the PhenX SDoH Collections. The Working Group helped fill this gap by selecting the Religious Behaviors and Congregational Support protocol. Despite Americans’ declining reliance on religion, understanding religiosity and spirituality is relevant to health outcomes. Racial differences may contribute to religious commitment; Black Americans are more likely than the American public to say that religion is important or very important to them (Nortey & Lipka, 2021). Religion informs behaviors and supports how people make decisions in day-to-day life, including health-related decisions. For example, religious service attendees trusted their faith leaders’ guidance on vaccines slightly more than public health officials during the COVID-19 pandemic (Nortey & Lipka, 2021). Most religious measures are from a Judeo-Christian perspective of religious and spirituality indicators. Spirituality measures may capture broad identity, behavior, and coping across religious beliefs and do not capture the systemic influences and activities of religion.

Relevance and applicability of these protocols to specific population groups needs to be established. Availability of SDoH protocols in Spanish and in languages other than English would increase their usability by non-English speaking participants. Cultural sensitivity testing may not have been done with diverse populations, which leads to researchers needing to assess whether the constructs in these protocols are relevant to their study populations. While the Toolkit includes general references about the use of these protocols, there may not be literature to identify with what population groups the protocols have been successfully used. These factors create opportunities for SDoH researchers to field the PhenX SDoH protocols and publish their studies to have more data for understanding health disparities.

Time Considerations

The Basic Protocol for “Using the PhenX Toolkit to Select and Implement SDoH Protocols” described in this article will take ∼15 to 20 min to complete, depending on the number of measurement protocols selected for addition to My Toolkit and the number of downloads the investigator selects. The breadth of searches for additional protocols relevant to the study design could also affect the time needed to identify desired protocols for My Toolkit. Additional time may be required for filtering search results, reviewing measurement protocol details, and comparing protocols of interest.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institutes of Health, Award Number U41HG007050. Co-funding was provided by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the Office of the Director, the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. In addition, prior funding has been provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Cancer Institute, and the NIH Tobacco Regulatory Science Program. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

The authors would like to acknowledge the guidance of the PhenX Steering Committee and the NIH-wide SDoH PhenX Toolkit workgroup. The authors would like to acknowledge the efforts of the overall National Human Genome Research Institute/RTI PhenX project team: Stephanie Calluori, Patricia Ceger, Michelle Engle, Iris Glaze, Aminah Isiaq, Tanya Reeve, Justin Waterfield, Lauren Wood, Xin Wu, and Cindy Changar. The authors would like to thank Grier Page of RTI for supporting the manuscript preparation effort.

Author Contributions

Cataia Ives : Project administration; writing original draft; writing review and editing. Michelle Krzyzanowski : Data curation; project administration; software; writing original draft. Vanessa Marshall : Conceptualization; writing review and editing. Keith Norris : Investigation; resources; validation; writing review and editing. Myles Cockburn : Investigation; resources; validation; writing review and editing. Keisha Bentley-Edwards : Investigation; resources; validation; writing review and editing. Dinushika Mohottige : Investigation; resources; validation; writing original draft. Keshia Pollack Porter : Investigation; resources; validation; writing review and editing. Denise Dillard : Investigation; resources; validation. Yochai Eisenberg : Investigation; resources; validation. Monik C. Jiménez : Investigation; resources; validation. Eliseo J. Pérez-Stable : Conceptualization. Nancy L. Jones : Conceptualization. Jyoti Dayal : Conceptualization. Deborah R. Maiese : Methodology. David Williams : Data curation; software. Tabitha P. Hendershot : Conceptualization; methodology; supervision; writing review and editing. Carol M. Hamilton : Conceptualization; funding acquisition; methodology; supervision; writing review and editing.

Conflict of Interest

Authors have no financial or personal relationship between themselves and others that might bias their work.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data were collected or analyzed in this study.

Literature Cited

- Adkins-Jackson, P. B., Chantarat, T., Bailey, Z. D., & Ponce, N. A. (2022). Measuring structural racism: A guide for epidemiologists and other health researchers. American Journal of Epidemiology , 191(4), 539–547. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwab239

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2019). 2018 national healthcare quality and disparities report. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr18/index.html

- All of Us Research Program. (2021). Social determinants of health survey. All of Us Research Hub. Retrieved July 13, 2023, from https://www.researchallofus.org/data-tools/survey-explorer/social-determinants-survey/

- Bailey, Z. D., Krieger, N., Agénor, M., Graves, J., Linos, N., & Bassett, M. T. (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet , 389(10077), 1453–1463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X

- Beech, B. M., Ford, C., Thorpe, R. J. Jr., Bruce, M. A., & Norris, K. C. (2021). Poverty, racism, and the public health crisis in America. Frontiers in Public Health , 9, 699049. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.699049

- Bird, S. T., & Bogart, L. M. (2001). Perceived race-based and socioeconomic status (SES)-based discrimination in interactions with health care providers. Ethnicity & Disease, 11(3), 554–563.

- Braveman, P. A., Arkin, E., Proctor, D., Kauh, T., & Holm, N. (2022). Systemic and structural racism: Definitions, examples, health damages, and approaches to dismantling. Health Affairs , 41(2), 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01394

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022). Why is addressing social determinants of health important for CDC and public health? Social Determinants of Health at CDC. Retrieved November 8, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/about/sdoh/addressing-sdoh.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). Social determinants of health. Public Health Professionals Gateway. Retrieved September 7, 2023, from https://cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/SDoH/index.html

- Cox, L. A., Hwang, S., Haines, J., Ramos, E. M., McCarty, C. A., Marazita, M. L., Engle, M. L., Hendershot, T., Pan, H. H., & Hamilton, C. M. (2021). Using the PhenX Toolkit to select standard measurement protocols for your research study. Current Protocols , 1(5), e149. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpz1.149

- Gómez, C. A., Kleinman, D. V., Pronk, N., Wrenn Gordon, G. L., Ochiai, E., Blakey, C., Johnson, A., & Brewer, K. H. (2021). Addressing health equity and social determinants of health through Healthy People 2030. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice, 27(Suppl 6), S249–S257. https://doi.org/10.1097/phh.0000000000001297

- Hacker, K., Auerbach, J., Ikeda, R., Philip, C., Houry, D., & SDoH Task Force. (2022). Social determinants of health—An approach taken at CDC. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice, 28(6), 589–594. https://doi.org/10.1097/phh.0000000000001626

- Haendel, M. A., Chute, C. G., Bennett, T. D., Eichmann, D. A., Guinney, J., Kibbe, W. A., Payne, P. R. O., Pfaff, E. R., Robinson, P. N., Saltz, J. H., Spratt, H., Suver, C., Wilbanks, J., Wilcox, A. B., Williams, A. E., Wu, C., Blacketer, C., Bradford, R. L., Cimino, J. J., Clark, M., … N3C Consortium. (2021). The National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C): Rationale, design, infrastructure, and deployment. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association , 28(3), 427–443. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa196

- Haendel, M. A., Housman, D., Mehta, H., Madlock-Brown, C., & Walden, A. (2021). Using National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) Data to Inform your Protocol Development [Webinar]. National COVID Cohort Collaborative. https://covid.cd2h.org/about/presentations.jsp

- Hamilton, C., Strader, L., Pratt, J., Maiese, D., Hendershot, T., Kwok, R. K., Hammond, J. A., Huggins, W., Jackman, D., Pan, H., Nettles, D. S., Beaty, T. H., Farrer, L. A., Kraft, P., Marazita, M. L., Ordovas, J. M., Pato, C. N., Spitz, M. R., Wagener, D., … Haines, J. (2011). The PhenX Toolkit: Get the most from your measures. American Journal of Epidemiology , 174(3), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr193

- Hausmann, L. R. M., Kressin, N. R., Hanusa, B. H., & Ibrahim, S. A. (2010). Perceived racial discrimination in health care and its association with patients’ healthcare experiences: Does the measure matter? Ethnicity & Disease, 20(1), 40–47. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48668251

- Heller, J. C., Fleming, P. J., Petteway, R. J., Givens, M., & Pollack Porter, K. M. (2023). Power up: A call for public health to recognize, analyze, and shift the balance in power relations to advance health and racial equity. American Journal of Public Health , 113(10), 1079–1082. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2023.307380

- Hill-Briggs, F., & Fitzpatrick, S. L. (2023). Overview of social determinants of health in the development of diabetes. Diabetes Care , 46(9), 1590–1598. https://doi.org/10.2337/dci23-0001

- Howard, S. D., Lee, K. L., Nathan, A. G., Wenger, H. C., Chin, M. H., & Cook, S. C. (2019). Healthcare experiences of transgender people of color. Journal of General Internal Medicine , 34, 2068–2074. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05179-0

- Krieger, N., Smith, K., Naishadham, D., Hartman, C., & Barbeau, E. M. (2005). Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science & Medicine, 61(7), 1576–1596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006

- Krzyzanowski, M. C., Terry, I., Williams, D., West, P., Gridley, L. N., & Hamilton, C. M. (2021). The PhenX Toolkit: Establishing standard measures for COVID-19 research. Current Protocols , 1(4), e111. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpz1.111

- Krzyzanowski, M. C., Nelms, M. D., Williams, D. N., Cox, L. A., Schoden, J. H., Ives, C. L., Brandow, A., Carroll, P., Felson, D., Norris, K., Cockburn, M. G., Huggins, W., Maiese, D., Gridley, L., West, P., Wu, X., Mandal, M., Pan, H., Jones, N., … Hamilton, C. (2022). PhenX presents bone and joint updates and expansion of social determinants of health [Poster presentation]. Annual Meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics, Los Angeles, CA.

- Krzyzanowski, M. C., Ives, C. L., Jones, N. L., Entwisle, B., Fernandez, A., Cullen, T. A., Darity, W. A. Jr., Fossett, M., Remington, P. L., Taualii, M., Wilkins, C. H., Pérez-Stable, E. J., Rajapakse, N., Breen, N., Zhang, X., Maiese, D. R., Hendershot, T. P., Mandal, M., Hwang, S. Y., … Hamilton, C. M. (2023). The PhenX Toolkit: Measurement protocols for assessment of social determinants of health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 65(3), 534–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2023.03.003

- Larrabee Sonderlund, A., Charifson, M., Schoenthaler, A., Carson, T., & Williams, N. J. (2022). Racialized economic segregation and health outcomes: A systematic review of studies that use the Index of Concentration at the Extremes for race, income, and their interaction. PloS One , 17(1), e0262962. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262962

- LaVeist, T. A., Nickerson, K. J., & Bowie, J. V. (2000). Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and White cardiac patients. Medical Care Research and Review , 57(Suppl 1), 146–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558700057001S07

- Lett, E., Logie, C. H., & Mohottige, D. (2023). Intersectionality as a lens for achieving kidney health justice. Nature Reviews Nephrology , 19, 353–354. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-023-00715-y

- Liao, Y., Bang, D., Cosgrove, S., Dulin, R., Harris, Z., Taylor, A., White, S., Yatabe, G., Liburd, L., Giles, W., & Division of Adult and Community Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2011). Surveillance of health status in minority communities - Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health Across the U.S. (REACH U.S.) Risk Factor Survey, United States, 2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Surveillance Summaries , 60(SS06), 1–41. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6006a1.htm

- Maiese, D., Hendershot, T., Strader, L. C., Wagener, D. K., Hammond, J. A., Huggins, B. W., Kwok, R. K., Hancock, D. B., Whitehead, N. S., Nettles, D. S., Pratt, J. G., Scott, M. S., Conway, K. P., Junkins, H. A., Ramos, E. M., & Hamilton, C. M. (2013). PhenX—Establishing a consensus process to select common measures for collaborative research. RTI Press. https://doi.org/10.3768/rtipress.2013.mr.0027.1310

- National Institute of Nursing Research. (n.d.). NIH-wide Social Determinants of Health Research Coordinating Committee. Research and Funding. Retrieved September 7, 2023, from https://www.ninr.nih.gov/researchandfunding/nih-SDoHrcc#tabs2

- National Institute of Nursing Research. (2023). Advancing social determinants of health research at NIH through cross-cutting collaboration. News and Notes NINR Newsletter. Retrieved September 7, 2023, from https://www.ninr.nih.gov/newsandinformation/newsandnotes/SDoH-rcc-001

- National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). (2017). NIMHD research framework. Retrieved June 14, 2023, from https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/research-framework/

- National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). (2022). National Institutes of Health minority health and health disparities strategic plan 2021–2025. Retrieved September 7, 2023, from https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/strategic-plan/

- National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). (2023). Structural racism and discrimination. Retrieved Nov 6, 2023, from https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/resources/understanding-health-disparities/srd.html

- National Institutes of Health, Office of Extramural Research. (2020). Notice announcing availability of data harmonization tools for social determinants of health (SDOH) via the PhenX Toolkit. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved July 14, 2023, from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-MD-21-003.html

- National Institutes of Health, Office of Extramural Research. (2021). Understanding and addressing the impact of structural racism and discrimination on minority health and health disparities (R01 Clinical Trial Optional). Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved November 8, 2023, from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-MD-21-004.html

- National Institutes of Health, Office of Extramural Research. (2023a). Addressing the impact of structural racism and discrimination on minority health and health disparities (R01 – Clinical Trial Optional). Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/par-23-112.html

- National Institutes of Health, Office of Extramural Research. (2023b). Estimates of funding for various Research, Condition, and Disease Categories (RCDC). NIH RePORT. Retrieved September 7, 2023, from https://report.nih.gov/funding/categorical-spending#/

- National Institutes of Health, Office of Strategic Coordination–The Common Fund. (2023). Community Partnerships to Advance Science for Society (ComPASS). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://commonfund.nih.gov/compass

- Nazroo, J. Y. (2003). The structuring of ethnic inequalities in health: Economic position, racial discrimination, and racism. American Journal of Public Health , 93(2), 277–284. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.2.277

- Nortey, J., & Lipka, M. (2021). Most Americans who go to religious services say they would trust their clergy's advice on COVID-19 vaccines. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/10/15/most-americans-who-go-to-religious-services-say-they-would-trust-their-clergys-advice-on-covid-19-vaccines/

- Pérez-Stable, E. J., & Collins, F. S. (2019). Science visioning in minority health and health disparities. American Journal of Public Health , 109(S1), S5. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.304962

- Scheim, A. I., & Bauer, G. R. (2019). The Intersectional Discrimination Index: Development and validation of measures of self-reported enacted and anticipated discrimination for intercategorical analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 226, 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.12.016

- B. D. Smedley, A. Y. Stith, A. R. Nelson (Eds.), & Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Institute of Medicine (2003). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12875

- Wilkinson, M. D., Dumontier, M., Aalbersberg, I. J., Appleton, G., Axton, M., Baak, A., Blomberg, N., Boiten, J.-W., daSilva Santos, L. B., Bourne, P. E., Bouwman, J., Brookes, A. J., Clark, T., Crosas, M., Dillo, I., Dumon, O., Edmunds, S., Evelo, C. T., Finkers, R., … Mons, B. (2016). The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data , 3, 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18

- Williams, D. R. (1999). Race, socioeconomic status, and health: The added effects of racism and discrimination. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences , 896(1), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.12.016

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization. Retrieved November 16, 2023, from https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health