Establishment and Culture of Human Intestinal Organoids Derived from Adult Stem Cells

Hans Clevers, Hans Clevers, Jens Puschhof, Jens Puschhof, Joep Beumer, Joep Beumer, Cayetano Pleguezuelos-Manzano, Cayetano Pleguezuelos-Manzano, Stieneke van den Brink, Stieneke van den Brink, Veerle Geurts, Veerle Geurts

adult stem cells

human intestinal organoids

organoid cryopreservation

organoid culture establishment

organoid differentiation

organoid immunofluorescence

organoid passage

single-cell clonal organoid culture

specialized organoid reagents

Abstract

Human intestinal organoids derived from adult stem cells are miniature ex vivo versions of the human intestinal epithelium. Intestinal organoids are useful tools for the study of intestinal physiology as well as many disease conditions. These organoids present numerous advantages compared to immortalized cell lines, but working with them requires dedicated techniques. The protocols described in this article provide a basic guide to establishment and maintenance of human intestinal organoids derived from small intestine and colon biopsies. Additionally, this article provides an overview of several downstream applications of human intestinal organoids. © 2020 The Authors.

Basic Protocol 1 : Establishment of human small intestine and colon organoid cultures from fresh biopsies

Basic Protocol 2 : Mechanical splitting, passage, and expansion of human intestinal organoids

Alternate Protocol : Differentiation of human intestinal organoids

Basic Protocol 3 : Cryopreservation and thawing of human intestinal organoids

Basic Protocol 4 : Immunofluorescence staining of human intestinal organoids

Basic Protocol 5 : Generation of single-cell clonal intestinal organoid cultures

Support Protocol 1 : Production of Wnt3A conditioned medium

Support Protocol 2 : Production of Rspo1 conditioned medium

Support Protocol 3 : Extraction of RNA from intestinal organoid cultures

INTRODUCTION

Adult stem cell (ASC)–derived organoids are miniature versions of epithelia that grow in three dimensions and can be expanded ex vivo. These mini-organs are derived from tissue biopsies and are entirely composed of primary epithelial cells, relying on the ability of the adult stem cells to expand indefinitely. They permit the study of epithelial physiology in a setup that closely resembles the in vivo situation. In contrast to animal models, adult stem cell organoids allow us to examine direct interactions between different cell types in a reductionist approach. Because they can be derived from humans, adult stem cell organoids capture the specific characteristics of human tissues. All these characteristics make them a powerful tool (Clevers, 2016).

Because organoids retain the characteristics of the native tissue from which they were derived, human intestinal organoids have been useful in the study of intestinal epithelial physiology and stem cell differentiation dynamics (Beumer et al., 2020 [human]; Farin et al., 2016 [mouse]). Additionally, human intestinal organoids have been used to study human disease (Fujii, Clevers, & Sato, 2019), usually following three approaches. (1) Disease modeling has been carried out by establishing organoid lines from monogenic disease patients, e.g., from cystic fibrosis (CFTR ; Dekkers et al., 2013), multiple intestinal atresia (TTC7A , Bigorgne et al., 2014), congenital diarrheal disorders (DGAT1 ; van Rijn et al., 2018). By repairing these mutations using CRISPR/Cas9-based genetic engineering in the patient-derived organoids, this technology might be used in future regenerative medicine approaches (Geurts et al., 2020; Schwank et al., 2013). (2) Introduction of mutations, again using CRISPR/Cas9 technologies, in healthy organoids allows molecular studies of different diseases such as cancer (Drost et al., 2015; Fujii, Matano, Nanki, & Sato, 2015). (3) Establishment of tumor and matched healthy organoid lines from colorectal cancer (CRC) patients allows study of treatment response and tumor heterogeneity (Drost & Clevers, 2018; van de Wetering et al., 2015). Furthermore, organoids have proven to be valuable tools for studying mutagenic processes in human physiology and disease (Blokzijl et al., 2016; Christensen et al., 2019; Pleguezuelos-Manzano et al., 2020).

The human intestinal epithelium functions as a physical barrier that separates the internal and external face of the intestinal tract. Because of this, the intestinal epithelium is in constant interplay with the immune environment. This interplay is highly important for maintenance of a homeostatic state, and its imbalance is often linked to disease. For this reason, human intestinal organoids have emerged as a great tool for studying the function of this epithelium and its relations with the immune component in disease (Bar-Ephraim, Kretzschmar, & Clevers, 2019), including celiac disease (Dieterich, Neurath, & Zopf, 2020; Freire et al., 2019) and ulcerative colitis (Nanki et al., 2020) among others. Moreover, human intestinal organoids can be useful in cancer immunotherapy research (Dijkstra et al., 2018).

This article describes how to establish organoid cultures from biopsies of human small intestine or colon (Basic Protocol 1) and how expand the organoid cultures ex vivo (Basic Protocol 2). An Alternate Protocol focuses on how to differentiate expanding intestinal organoids (predominantly composed of stem cells and transit-amplifying cells) towards a more mature cell type composition (i.e., enterocytes, enteroendocrine cells, or goblet cells). Organoid cryopreservation and thawing are discussed in Basic Protocol 3. Several methods then exemplify how to perform some of the most common downstream applications/readouts with organoids. Basic Protocol 4 describes immunofluorescence staining for fluorescence/confocal imaging. In light of the increasing importance of CRISPR/Cas9-engineered organoids and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of organoid lines, a protocol is provided for single-cell clonal outgrowth of intestinal organoids (Basic Protocol 5), which is of key importance for both applications. The production of two essential medium components, Wnt3A and Rspo1 conditioned medium, is detailed in Support Protocols 1 and 2. Finally, these protocols are supplemented by a method for extracting organoid RNA (Support Protocol 3) that can be used for gene expression readouts like quantitative real-time PCR or RNA sequencing.

STRATEGIC PLANNING

Organoid lines can be established from biopsies (Basic Protocol 1) or obtained from a biobank or the research community. From biopsies, organoids can normally be derived in sufficient quantities for extensive experimentation and storage within a month. Established lines can be shipped on dry ice and used for experiments 1-2 weeks after thawing. Single-nucleotide polymorphism fingerprinting or comparable methods should be used to confirm line identity over time. As with cell lines, mycoplasma tests should be performed regularly. The use of patient-derived material should in all cases comply with the ethical regulations and guidelines of the relevant institutional boards. Written informed consent is required from all donors.

General Considerations

Human organoid lines present some degree of heterogeneity due to inter- and intra-donor variability. Particularly, the expansion ability or “stemness” of some lines is higher than others, and this usually inversely correlates with their ability to achieve full differentiation. This should be taken into consideration when selecting a pre-established organoid line or when characterizing a newly established line. Furthermore, there are some differences between organoids derived from different regions of the intestinal tract, reflecting intrinsic differences between these epithelial regions in vivo. Generally, duodenal organoids show a higher stemness ex vivo compared to those from other regions, and therefore are easier to expand. A key factor to organoid culture expansion is activation of the Wnt pathway. To achieve this, two different Wnt sources (Wnt3A conditioned medium and Wnt surrogate molecules) have been successfully applied. Wnt3A conditioned medium (Wnt3A-CM, see Support Protocol 1) is a more economical source of Wnt ligands, but yields a lower level of Wnt activation and may suffer from batch-to-batch variability. In contrast, synthetic Wnt surrogate (Miao et al., 2020) can achieve high activation of the Wnt pathway, fueling faster organoid expansion in some organoid systems. The use of Wnt surrogate is recommended especially for human colon organoid cultures and when growing single-cell clonal cultures.

Preparation and Considerations Before Starting Organoid Work

Basement membrane extract (BME) should be thawed overnight at 4°C before starting any of the protocols described. Once thawed, it should be kept at 4°C at every moment. Freeze-thaw cycles are not recommended. Multiwell cell culture plates should be prewarmed at 37°C for several hours before use for organoid culture. This will help the liquid BME-organoid solution solidify on the culture plate.

General Consumables and Equipment for Organoid Culture

General consumables include sterile 1.5-, 15-, and 50-ml plastic tubes; multiwell plates in different well formats (6, 12, 24, and 48 wells); micropipette tips; and serological pipettes. General equipment includes a Class II biosafety cabinet, centrifuge, microcentrifuge, inverted light microscope, and 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C.

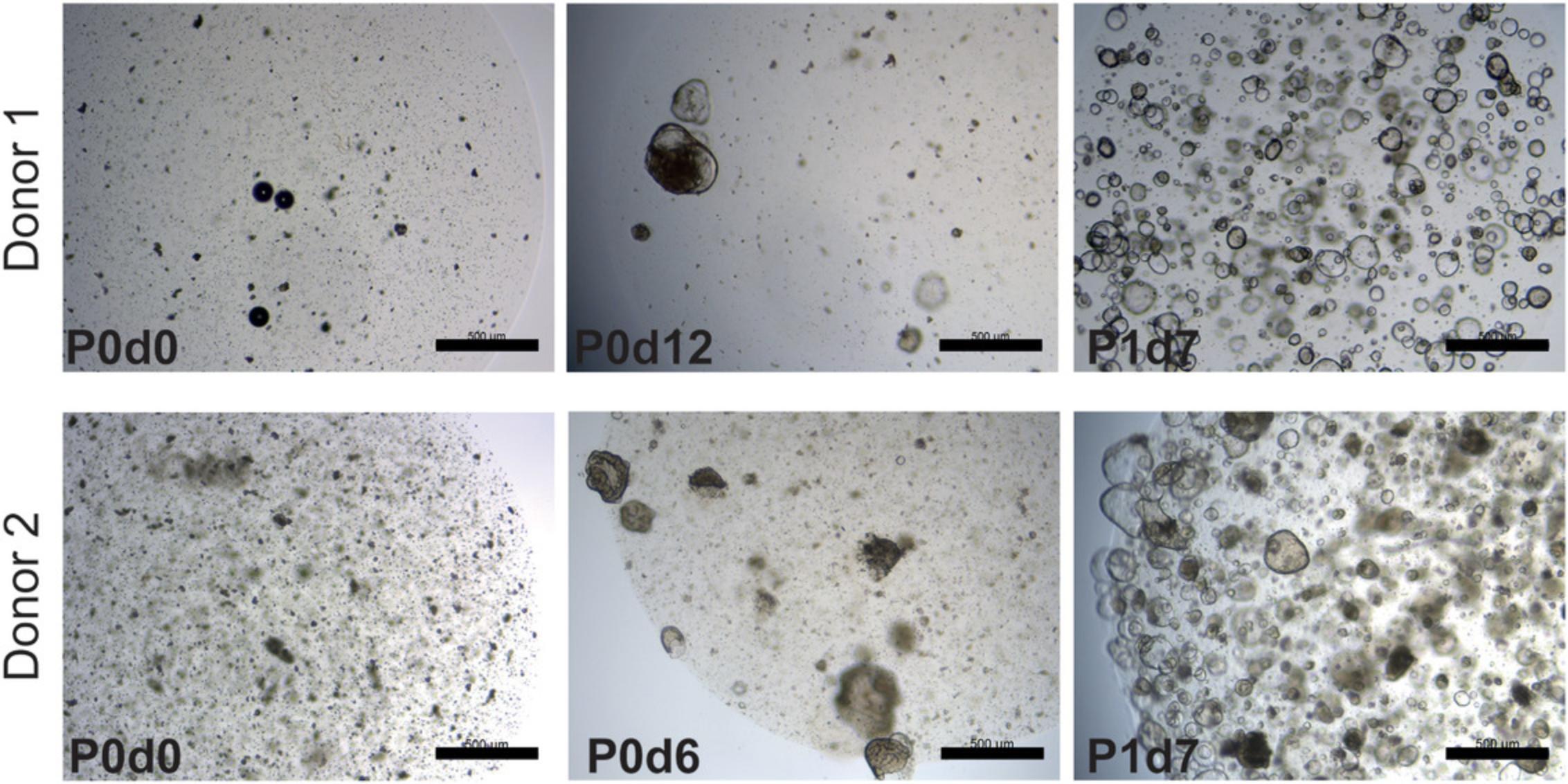

Basic Protocol 1: ESTABLISHMENT OF HUMAN SMALL INTESTINE AND COLON ORGANOID CULTURES FROM FRESH BIOPSIES

This protocol describes a method for establishing human intestinal ASC-derived organoid cultures from fresh biopsies of small intestine or colon. Tissue is dissociated into small epithelial fragments that are embedded into extracellular matrix “domes” using basement membrane extract (BME) and then supplemented with medium containing growth factors for organoid expansion.

Small intestine and colon biopsies are both suitable organoid culture sources. Because organoids maintain region-specific characteristics, pooling biopsies from different intestinal regions or different donors is not recommended. In the case of CRC biopsies, a paired normal sample should be collected from surrounding healthy tissue.

Materials

-

Fresh tissue biopsy from human small intestine or colon (healthy or tumor tissue)

-

70% (v/v) ethanol

-

AdvDMEM+++ (see recipe)

-

Primocin (InvivoGen, cat. no. ant-pm-1)

-

Collagenase type II (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. C9407-1)

-

Y-27632 Rho kinase inhibitor (RhoKi; Abmole, cat. no. Y-27632)

-

Cultrex reduced-growth-factor basement membrane extract (BME), type 2, Pathclear (R&D Systems/Bio-Techne, cat. no. 3533-001)

-

Red blood cell lysis solution (Gibco, cat. no. A1049201)

-

Expansion medium (see recipe)

-

15- and 50-ml Falcon tubes

-

10-cm Petri dish

-

Disposable scalpels (VWR, cat. no. HERE1110810)

-

Parafilm (Sigma Aldrich, cat. no. P7793-1EA)

-

Orbital shaker

-

100-µm cell strainer (Green Bioresearch, cat. no. 542000)

-

5-ml pipet

-

24-well cell culture plate (Greiner Bio-One, cat. no. 662 102)

Prepare cell suspension

1.Collect tissue sample from the tissue sample source site in a 50-ml Falcon tube containing 25 ml AdvDMEM+++ and 100 μg/ml Primocin. Keep at 4°C until use.

2.Start up the biosafety cabinet. Disinfect the work area surface and pipets by spraying with 70% ethanol and allow to air dry.

3.Prepare fresh digestion medium for each tissue sample: Aliquot 5 ml AdvDMEM+++ into a 15-ml plastic tube and add 5 mg/ml collagenase type II and 10 µM RhoKi. Mix by inverting and store on ice until use.

4.Transfer tissue to a 10-cm Petri dish.

5.Using two scalpels, mince tissue into pieces of ∼1 mm3. Add the 5 ml digestion medium and mix by pipetting.

6.Transfer digestion medium with tissue to a 15-ml plastic tube. Rinse the dish with the medium, returning the medium and all tissue pieces to the tube.

7.Close tube lid and seal with Parafilm. Place tube tilted at a low angle on an orbital shaker. Digest tissue for 30 to 45 min at 37°C and 140 rpm.

8.Pipet the digested tissue onto a 100-µm cell strainer on a 50-ml plastic tube. Use a 5-ml pipet to help pass the cell suspension through the filter.

9.Rinse the strainer with 5 ml AdvDMEM+++ and transfer the solution (total 10 ml) to a fresh 15-ml plastic tube.

10.Centrifuge 5 min at 450 × g , 4°C. Aspirate the supernatant.

11.Wash pellet three times with 10 ml AdvDMEM+++. Each time, spin 5 min at 450 × g , 4°C, and aspirate the supernatant.

12.Resuspend final pellet in undiluted BME.

Plate cells and grow as organoids

13.Plate 50 µl cell suspension per well as multiple ∼15-µl droplets in a prewarmed 24-well cell culture plate.

14.Place plate upside-down in a 37°C, 5% CO2 cell culture incubator and allow droplets to solidify for 20 min.

15.Carefully add 500 µl expansion medium supplemented with 10 µM RhoKi to each well and return the plate to the incubator.

16.After ∼1 week, expand organoids by mechanical disruption and splitting (see Basic Protocol 2).

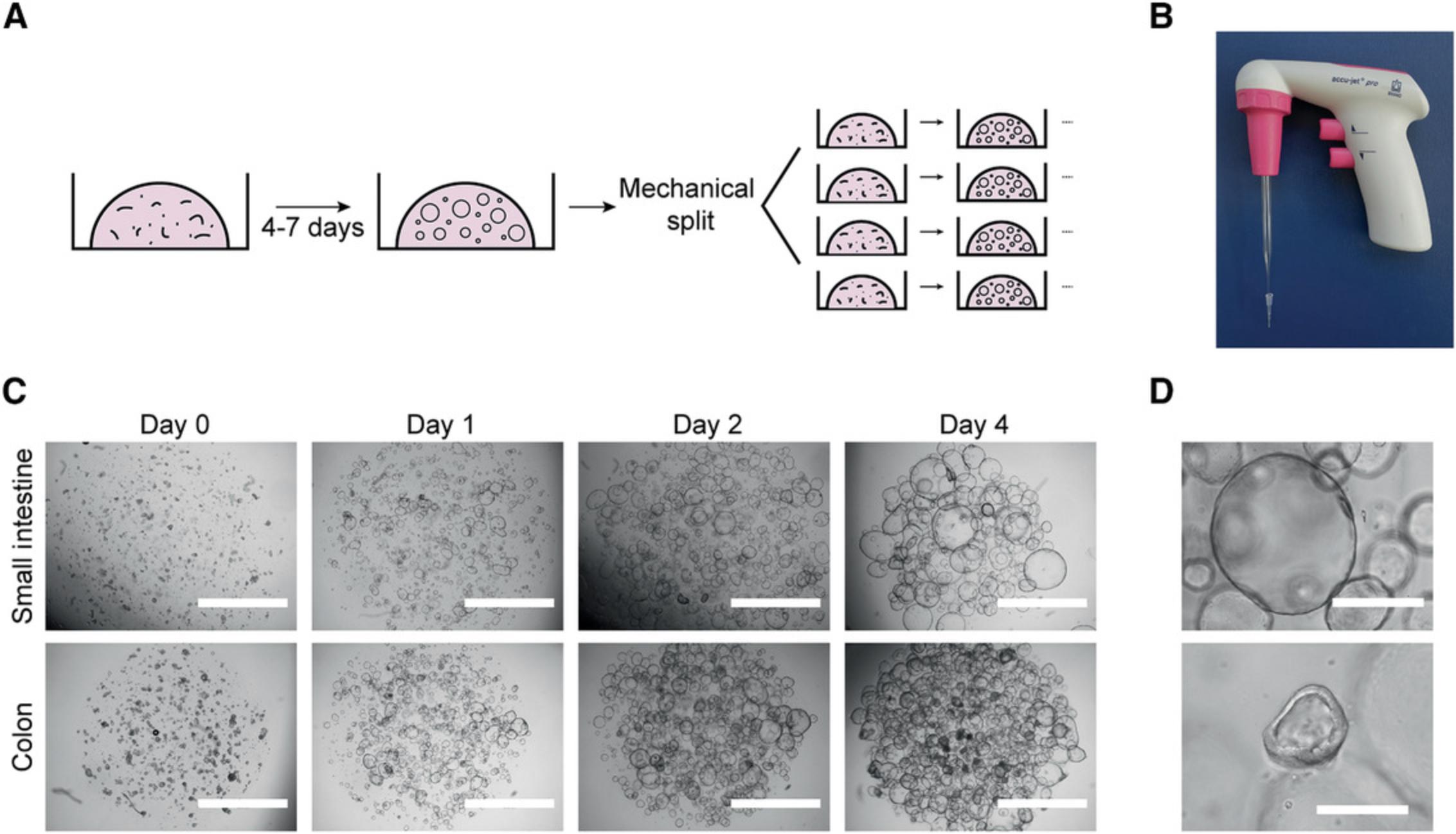

Basic Protocol 2: MECHANICAL SPLITTING, PASSAGE, AND EXPANSION OF HUMAN INTESTINAL ORGANOIDS

The process of mechanical splitting and passage is similar for organoids from human small intestine and colon due to the high similarity of these two organoid types. In short, organoids are recovered from the basement membrane matrix and broken mechanically into smaller fragments. The fragments are then resuspended in fresh BME and replated. They will self-assemble as new organoids, and the stem cells and transit-amplifying cells present in them will continue to proliferate, giving rise to a fully grown expanded organoid culture (Fig. 2A).

Additional materials (also see Basic Protocol 1)

- Established organoid culture (see Basic Protocol 1 if first passage, or this protocol if later passage)

- Sterile plugged glass Pasteur pipette (VWR, cat. no. 14672-400)

- Sterile 10-μl pipette tips

- Mechanical pipetter

1.Remove medium from one well of a 12- or 24-well plate of established organoid cultures.

| Plate format | BME/well (μl) | Domes/well | Culture medium/well (ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 wells | 200 | 10-15 | 2 |

| 12 wells | 100 | 5-7 | 1 |

| 24 wells | 50 | 1-3 | 0.5 |

| 48 wells | 25 | 1 | 0.25 |

| 96 wells | 5-10 | 1 | 0.1 |

2.Using a P1000 pipette, flush the organoids with 1 ml ice-cold AdvDMEM+++ to disrupt the BME droplets. Collect the organoids and transfer to a 15-ml plastic tube containing 4 ml ice-cold AdvDMEM+++.

3.Centrifuge the organoids 5 min at 450 × g , 4°C. Remove supernatant.

4.Resuspend pellet in 1 ml ice-cold AdvDMEM+++ using a P1000 pipette.

5.Attach a sterile 10-μl pipette tip to the tip of a glass Pasteur pipette (Fig. 2B). Pass the organoids through the pipette opening five to ten times until large clumps are no longer visible.

6.Add 4 ml ice-cold AdvDMEM+++ and centrifuge 5 min at 450 × g , 4°C. Remove supernatant.

7.Resuspend pellet in 300-400 μl BME using a P1000 pipette.

8.Dispense 100 μl suspension per well as multiple ∼15-μl droplets in a prewarmed 12-well culture plate (Fig. 2C).

9.Flip the plate upside down and place plate in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 20 min to let domes solidify.

10.Add 1 ml expansion medium and keep in the incubator, refreshing the medium every 2-3 days.

11.After 7 days, expand organoids further by repeating this process.

Alternate Protocol: DIFFERENTIATION OF HUMAN INTESTINAL ORGANOIDS

This protocol describes ways to differentiate organoids to the various cell types of the small intestinal and colonic epithelia. By withdrawing growth factors, which enforce a stem cell state, and adding components that skew differentiation trajectories, different types and proportions of mature cells can be obtained within 5 days. These mature cell types can be used for functional studies of the human gut epithelium.

Additional materials (also see Basic Protocol 1)

- Established human intestinal organoid culture (see Basic Protocol 2)

- Differentiation medium (see recipe)

1.Aspirate medium from one well containing an established organoid culture grown to an average size of 100 µm (usually 5 days after splitting).

2.Add 1 ml prewarmed AdvDMEM+++ and incubate at least 15 min in the 37°C incubator to allow diffusion of growth factors from the BME domes.

3.Aspirate medium from the well and add 1 ml prewarmed differentiation medium per well of a 12-well plate. Return to incubator overnight.

| Medium | Reference | Expected outcome | Special considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ENR | Sato et al. (2011) | Enterocytes, EECs, TACs, goblet cells | Generic differentiation medium for broad coverage of differentiated cell types, with particular enrichment of enterocytes |

| ENR+Notchi | Goblet cells | Goblet cell differentiation | |

| ENR+MEKi+Notchi | Beumer et al. (2018) | EECs (crypt/lower villus state) | Enteroendocrine cell differentiation inducing a crypt hormone profile |

| ER+MEKi+Notchi+ BMP4+BMP2 | Beumer et al. (2018) | EECs (upper villus state) | Enteroendocrine cell differentiation inducing an upper villus hormone profile |

- a

For full composition of media, see Reagents and Solutions.

- b

Abbreviations: BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; EEC, enteroendocrine cell; ENR, EGF-Noggin-Rspo1; MEK, p38 MAP kinase; TAC, transit-amplifying cell.

4.Refresh differentiation medium the next day to wash away any residual growth factors. Continue to refresh differentiation medium every 2-3 days.

Basic Protocol 3: CRYOPRESERVATION AND THAWING OF HUMAN ORGANOID CULTURES

This protocol details the steps for cryopreservation and thawing of intestinal and colon organoids. Cryopreservation is especially advisable when storing organoids for years in liquid nitrogen, but also for shipping organoid lines on dry ice. Briefly, organoids are freed from the BME and resuspended in freezing medium. To restart the cultures, organoids are carefully thawed, washed, and plated in BME domes. Thawed organoids are passaged according to Basic Protocol 2.After one passage, organoids should have normal growth characteristics and can be used for any downstream assay.

Additional materials (also see Basic Protocol 1)

- Established organoid culture (see Basic Protocol 2)

- 2× freezing medium (see recipe)

- Cryopreservation tubes

- Freezing container

- 37°C water bath

Freeze organoids

1.Passage organoids 2-3 days before cryopreservation (see Basic Protocol 2).

2.Remove medium from one well of a 12-well plate of established organoid culture.

3.Using a P1000 pipette, flush the organoids with 1 ml ice-cold AdvDMEM+++ to disrupt the BME droplets. Collect the organoids and transfer to a 15-ml plastic tube containing 4 ml ice-cold AdvDMEM+++.

4.Centrifuge organoids 5 min at 450 × g , 4°C. Remove supernatant.

5.Resuspend pellet in 1 volume of ice-cold AdvDMEM+++ using a P1000 pipette, then add 1 volume of 2× freezing medium dropwise under constant shaking.

6.Transfer 1-ml aliquots of organoid suspension to properly labeled cryopreservation tubes.

7.Place tubes in a freezing container and freeze at −80°C overnight.

8.Transfer tubes to a liquid nitrogen container.

Thaw stocks

9.Prepare AdvDMEM+++ and labeled 15-ml tubes while organoids are still frozen to minimize thawing and processing times.

10.Transport tubes of organoids from liquid nitrogen to a flow cabinet on dry ice.

11.Thaw tubes in a water bath at 37°C.

12.Transfer thawed organoid suspension to 15-ml Falcon tubes (one per cryotube) and add 10 ml AdvDMEM+++ dropwise under constant shaking.

13.Centrifuge 5 min at 450 × g , 4°C. Remove supernatant.

14.Resuspend each cell pellet in 100 μl BME using a P200 pipette, being careful to avoid bubble formation.

15.Dispense as ∼15-µl drops in a well of a 12-well cell culture suspension plate.

16.Place the plate upside-down in the incubator for 20 min to let domes solidify.

17.Add expansion medium and keep in the incubator. Refresh medium every 2-3 days.

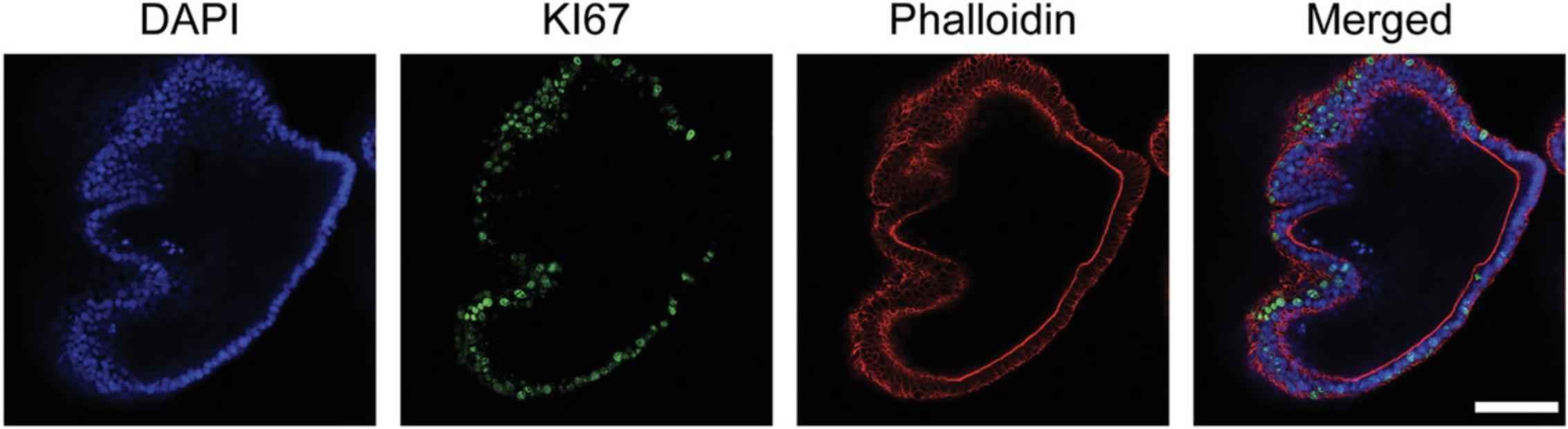

Basic Protocol 4: IMMUNOFLUORESCENCE STAINING OF HUMAN INTESTINAL ORGANOIDS

This protocol describes a way to perform immunofluorescence staining compatible with fluorescence and confocal microscopy. For this purpose, organoids must first be released from the BME without disrupting their 3D architecture. Subsequent fixation, permeabilization, blocking, staining, and washes are performed with the organoids in suspension. This method can be applied to organoids that have been subjected to various experimental conditions.

Materials

-

Established organoid culture (see Basic Protocol 2)

-

Fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. F7524)

-

Cell Recovery Solution (Corning, cat. no. 354253)

-

Dispase (StemCell Technologies, cat. no. 07923; optional)

-

4% (v/v) formaldehyde in aqueous buffer

-

Permeabilization solution (see recipe)

-

Blocking solution (see recipe)

-

Mouse anti–human KI67 primary antibody (BD Pharmigen, cat. no. 550609)

-

PBS

-

Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody (Invitrogen, cat. no. A-21202)

-

Phalloidin-Atto 647N (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 65906)

-

DAPI

-

ProLong Gold Antifade Mounting solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. P36934)

-

Vaseline petroleum jelly

-

Clear nail polish

-

Sterile scissors

-

1000-μl pipette tips

-

1.5-ml microcentrifuge plastic tubes

-

Brightfield microscope

-

Tube roller

-

300-μl low-retention filter tips (Greiner Bio-One, cat. no. 738 265)

-

96-well black glass-bottom plate (Greiner bio-one, cat. no. 655892)

-

Microscope slides and cover slips

Release organoids

1.Remove and discard medium from one well containing organoids.

2.With sterile scissors, cut the opening of a 1000-μl pipette tip 2-3 mm from its end. Coat the tip and a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube with FBS by pipetting 1 ml up and down once.

3.Using the coated pipette tip, pipette 1 ml Cell Recovery Solution to the well, collect the organoids, and transfer to the coated microcentrifuge tube.

4.Incubate on ice for 20-30 min, inverting regularly to prevent clumping and heterogeneous BME dissociation.

5.Monitor BME dissociation under a microscope, stopping when BME is sufficiently dissolved.

6.Let organoids settle by gravity to the bottom of the tube and remove the supernatant.

Fix and permeabilize organoids

7.Add 1 ml of 4% formaldehyde and incubate 16 hr at 4°C (or 2 hr at room temperature) with constant rolling of the tube to ensure homogeneous fixation. Let organoids settle by gravity and remove supernatant.

8.Add 1 ml permeabilization solution and incubate with constant rolling for 30 min at 4°C. Let organoids settle by gravity and remove supernatant.

Stain organoids

9.Add 1 ml blocking solution and incubate 15 min at room temperature under constant rolling. Let organoids settle by gravity and remove supernatant.

10.Add 200 µl of 500 ng/ml mouse anti–human KI67 primary antibody in blocking solution and incubate for 16 hr at 4°C under constant rolling. Let organoids settle by gravity and remove supernatant.

11.Resuspend pellet in 1 ml PBS and incubate 10 min at room temperature with constant rolling. Let organoids settle by gravity and remove supernatant. Repeat wash two more times.

12.Add 200 µl of 4 µg/ml Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody, 10 nM phalloidin-Atto 647N, and 2 µg/ml DAPI in blocking solution and incubate 1-2 hr in the dark at room temperature with constant rolling.

13.Wash three times as in step 11.

14.Wash once with Milli-Q-purified water to prevent crystal formation.

15.Cut the tip of a low-retention 300-μl tip 2-3 mm from its end and then coat the tip with FBS by pipetting 200 μl up and down once.

16a. For imaging in 96-well plates : Use the coated tip to resuspend organoids in 150-200 μl PBS and transfer them to one well of a 96-well black glass-bottom plate. For optimal results, image samples immediately after staining (Fig. 4).

16b. For imaging on microscope slides : Use the coated tip to resuspend organoids in 50 μl ProLong Gold mounting solution and transfer them to a microscope slide. Apply Vaseline at the edges of the slide so that the coverslip does not disrupt organoid structure after mounting. Seal the slide using nail polish.

Basic Protocol 5: GENERATION OF SINGLE-CELL CLONAL INTESTINAL ORGANOID CULTURES

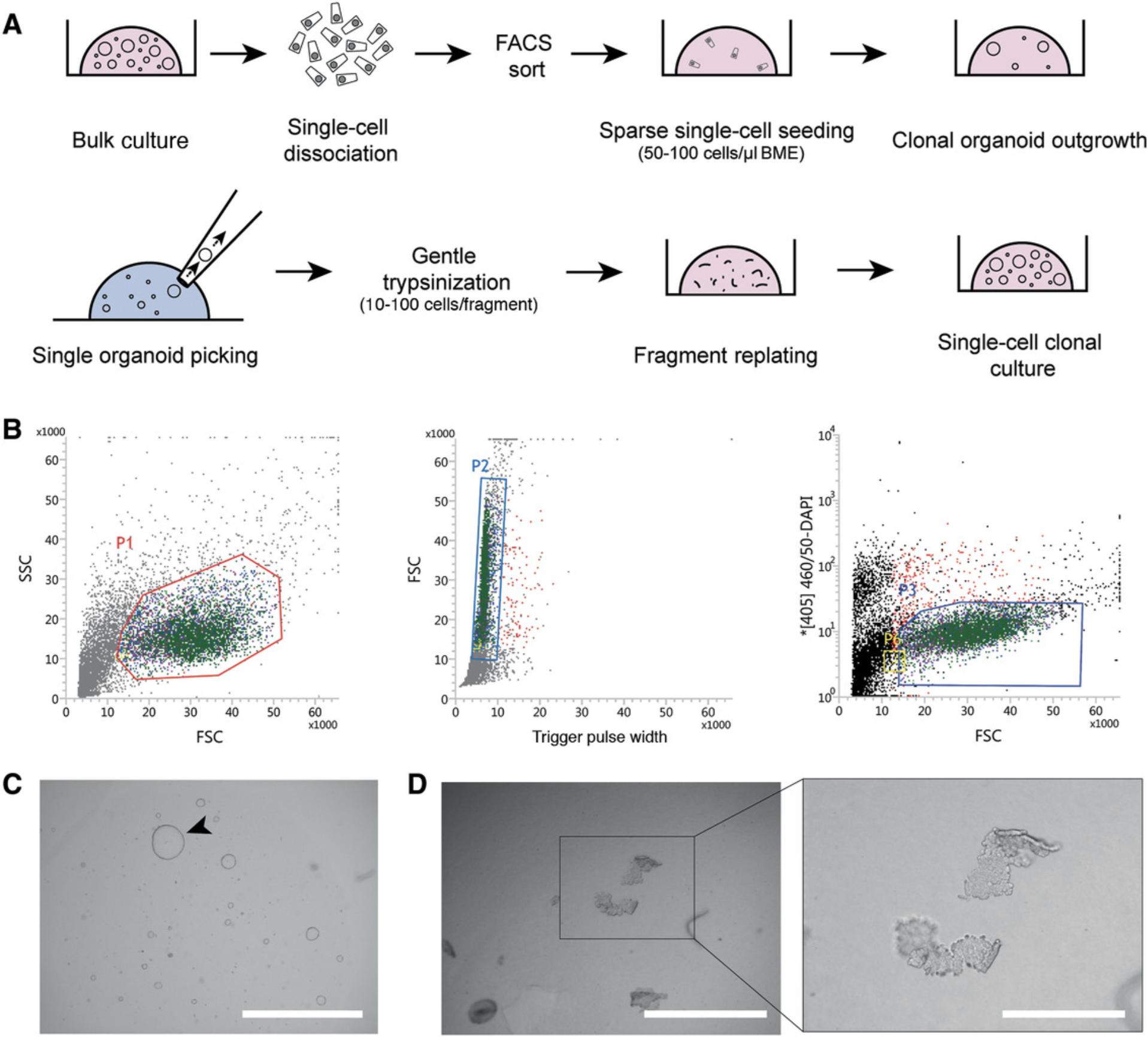

Many downstream applications of organoid cultures (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9 genetic engineering, whole-genome sequencing) require generation of clonal cultures derived from single cells. To efficiently generate such cultures, organoids are first dissociated to single cells and seeded sparsely. After 10-15 days, individual organoids are picked using a pipette tip, gently disrupted by enzymatic means, and reseeded. After this step, grown organoids can be mechanically split following Basic Protocol 2.For a general overview, see Figure 5A. This protocol can be carried out using established organoids from Basic Protocol 2 or organoids subjected to various experimental conditions, like genetic engineering, treatment with mutagens, or other experimental setups requiring WGS.

Additional materials (also see Basic Protocols 1 and 4)

-

Established organoid culture (see Basic Protocol 2)

-

1× TrypLE Express Enzyme, phenol red (Gibco, cat. no. 12605036)

-

37°C water bath

-

Sterile plugged Pasteur glass pipettes and automated pipetter

-

Sterile 10-μl pipette tips

-

Flow cytometry tubes with 35-µm strainer cups (Corning, cat. no. 08-771-23)

-

Flow cytometer

-

12- and 48-well cell culture plates (Greiner Bio-One, cat. nos. 665 102 and 677 102)

-

Sterile 100-mm cell culture dish

Prepare organoids

1.Remove medium from one well of a 12-well plate culture of established organoid culture.

2.Using a P1000 pipette, flush organoids from the well with 1 ml ice-cold AdvDMEM+++ to disrupt the BME droplets. Collect the organoids and transfer to a 15-ml centrifuge tube containing 4 ml ice-cold AdvDMEM+++.

3.Centrifuge 5 min at 450 × g , 4°C. Remove supernatant.

4.Resuspend cell pellet in 1 ml prewarmed (37°C) TrpLE.

5.Incubate 5 min in a 37°C water bath, vortexing at regular intervals to increase dissociation. Check progress regularly under a microscope, and stop once the majority of fragments consist of single cells.

6.Coat a plugged glass Pasteur pipette with FBS to prevent cells from sticking to the glass. Connect a sterile 10-μl tip to the Pasteur pipette and use to mechanically disrupt the organoid fragments to obtain single cells (also see Basic Protocol 2, step 5).

7.Check cell suspension under the microscope. If organoids are not dissociated into single cells, repeat steps 5 and 6.

8.Add 4 ml ice-cold AdvDMEM+++ with 10 µM RhoKi to the cells.

9.Move a small fraction of cells to another tube to use as a DAPI-negative control in the FACS gating.

10.Centrifuge for 5 min at 450 × g , 4°C. Remove supernatant.

11.Resuspend cells in 0.5 ml ice-cold AdvDMEM+++ supplemented with 10 µM RhoKi and 2 µg/ml DAPI. Omit DAPI in the negative control sample.

12.Pass cells through the strainer of a 35-μm mesh-cupped flow cytometry tube. Transport cells to the flow cytometer on ice and protected from light.

Perform sorting and start cultures from single live cells

13.Sort living cells (DAPI-negative) into a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube containing 0.5 ml AdvDMEM+++ supplemented with 10 µM RhoKi (Fig. 5B).

-

Use FSC and SSC to gate intact epithelial cells with intact morphology (Fig.5B, left panel, P1).

-

On the gated population, use FSC and Trigger Pulse Width to select single cells and deplete cell duplets or triplets (Fig.5B, middle panel, P2).

-

Use the [405]460/50-DAPI channel to gate and sort living DAPI-negative cells (Fig.5B, right panel, P3).

-

At this step, note the number of cells sorted in the tube in order to calculate seeding cell density in the following steps.

14.Centrifuge cells 5 min at 450 × g , 4°C. Remove supernatant.

15.Resuspend cells homogeneously in BME to a density of 50-100 cells/µl. Pipette cells in ∼15-µl domes in a 12-well plate.

16.Place the plate upside-down in the incubator for 20 min to let the domes solidify.

17.Add expansion medium supplemented with 10 µM RhoKi and keep in the incubator, refreshing the medium (with RhoKi) every 2-3 days.

Isolate and expand clonal organoid cultures

18.Remove medium from the organoid well. Collect organoids in 1 ml Cell Recovery Solution and incubate on ice for 30 min.

19.Pipette solution containing organoids in ∼500-µl drops in a sterile 100-mm cell culture dish.

20.Place the plate under a brightfield microscope and open the lid.

21.Using a P20 pipette, pick individual organoids from the drop and transfer each one to a separate 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube containing 300 µl TrypLE at 4°C.

22.Incubate in a 37°C water bath for 1 min.

23.Add 700 µl AdvDMEM+++ containing 10 µM RhoKi and pipette up and down three to five times using a P1000 pipette.

24.Centrifuge 5 min at 500 × g , 4°C. Remove supernatant.

25.Resuspend in 20 µl BME and seed in a well of a 48-well plate (Fig. 4D).

26.Add expansion medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml Primocin and 10 µM RhoKi.

27.After organoids grow out, pass them as in Basic Protocol 2.

Support Protocol 1: PRODUCTION OF Wnt3A CONDITIONED MEDIUM

Wnt3A-CM is an important component of the human intestinal organoid expansion medium. Its role in activating the Wnt pathway is key to maintenance of the stem cell population. Thus, the production of high-quality Wnt3A-CM is essential for successful establishment and culture of human intestinal organoids.

Materials

-

L-Wnt-3A cells from frozen cryovial (from a T25 flask cultured to 95%-100% confluence) (provided upon request and after material transfer agreement)

-

DMEM++ (see recipe)

-

Zeocin (Gibco, cat. no. R25001)

-

1× TrypLE Express Enzyme, phenol red (Gibco, cat. no. 12605036)

-

HEK 293-STF cells (ATCC, CRL-3249)

-

T175 cell culture flasks (Greiner Bio-One, cat. no. 661160)

-

37°C, 5% CO2 cell culture incubator

-

145-mm cell culture dishes (Greiner Bio-One, cat. no. 639160)

-

0.22-µm Stericup-GP filter (polyethersulfone, 500 ml, radio-sterilized; Millipore, cat. no. SCGPU05RE)

1.Start L-Wnt-3A cell culture from a frozen cryovial. Seed cells in a T175 flask with 20 ml DMEM++ supplemented with 125 µg/ml Zeocin. Grow at 37°C and 5% CO2 until the culture reaches 90%-100% confluence (~3-4 days).

2.Split cells to two T175 flasks using TrypLE and grow cells in DMEM++ with 125 µg/ml Zeocin at 37°C and 5% CO2 until they reach 90%-100% confluence (~3-4 days).

3.Split cells to a total of twelve T175 flasks. Add DMEM++ supplemented with 125 µg/ml Zeocin to two flasks and use these for a new round of Wnt3A-CM production (step 2). Add DMEM++ without Zeocin to the other ten flasks and use these for steps 4-7.

4.Allow cultures in the ten flasks to grow to confluence (~1 week).

5.Trypsinize cultures, pool the cells, and seed in sixty 145-cm2 dishes in 20 ml DMEM++ without Zeocin per plate. Incubate cells for 1 week at 37°C and 5% CO2.

6.Harvest medium and centrifuge for 5 min at 450 × g , 4°C.

7.Collect supernatant and pass through a 0.22-µm Stericup-GP filter.

8.Test the quality of every batch of Wnt3A-CM using a luciferase-based assay in the HEK 293T-STF Wnt reporter cell line (Xu et al., 2004).

Support Protocol 2: PRODUCTION OF Rspo1 CONDITIONED MEDIUM

Rspo1-CM is used to prepare organoid medium as well as all of the differentiation media described here. The presence of Rspo1 in organoid expansion medium results in a synergistic increase in Wnt pathway activation levels compared to those achieved by Wnt3A-CM alone. Thus, Rspo1-CM is another key component of the medium used for establishment and expansion of human intestinal organoids.

Additional materials (also see Support Protocol 1)

- 293T-HA-RspoI Fc cells from frozen cryovial (from a T25 flask cultured to 95%-100% confluence) (R&D Systems, cat. no. 3710-001-01)

- T75 cell culture flasks (Greiner Bio-one, cat. no. 658170)

1.Start 293T-HA-RspoI Fc cell culture from a frozen cryovial. Seed cells in a T75 flask with 20 ml DMEM++ supplemented with 300 µg/ml Zeocin. Grow at 37°C and 5% CO2 until the culture reaches 90%-100% confluence.

2.Split cells to two T175 flasks using TrypLE and grow cells in DMEM++ with 300 µg/ml Zeocin at 37°C and 5% CO2 until they reach 90%-100% confluence.

3.Split cells to a total of twelve T175 flasks. Add DMEM++ supplemented with 300 µg/ml Zeocin to two flasks and use these for a new round of Rspo1-CM production (step 2). Add DMEM++ without Zeocin to the other ten flasks and use these for steps 4-6.

4.Grow cells in the ten flasks to 75% confluence (2-3 days).

5.Remove DMEM++ from the culture and add 50 ml serum-free AdvDMEM+++ without Zeocin per flask. Incubate cells for 1 week at 37°C and 5% CO2.

6.Harvest medium and centrifuge for 5 min at 450 × g , 4°C.

7.Collect supernatant and pass through a 0.22-µm Stericup-GP filter.

8.Test the quality of every batch of Rspo1-CM using a luciferase-based assay in the HEK 293T-STF Wnt reporter cell line.

Support Protocol 3: EXTRACTION OF RNA FROM INTESTINAL ORGANOID CULTURES

This protocol can be used with established organoid cultures, including those subjected to various experimental conditions.

Materials

- Established organoid culture (see Basic Protocol 2)

- Column-based extraction kit (RNAeasy Mini Kit, Qiagen, cat. no. 74104)

- Freshly prepared 70% (v/v) ethanol

- RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen, cat. no. 79254)

- RNase-free 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes

1.Remove medium from organoid well and dissolve the BME drop containing the organoids directly in 350 µl RLT buffer from the RNAeasy Mini Kit. Pipet several times up and down and transfer the suspension to a 15-ml plastic tube.

2.Mix the resulting solution 1:1 (v/v) with freshly prepared 70% ethanol and vortex.

3.Isolate RNA according to the manufacturer's instructions, starting with step 4 of “Protocol: Purification of Total RNA from Animal Cells Using Spin Technology” from the Qiagen RNAeasy Handbook Guide (https://www.qiagen.com/ie/resources/resourcedetail?id=14e7cf6e-521a-4cf7-8cbc-bf9f6fa33e24&lang=en).

4.Elute in 30 µl RNase-free water.

REAGENTS AND SOLUTIONS

AdvDMEM+++

- Advanced Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium/F12 (Gibco, cat. no. 12634-010)

- 10 mM HEPES (Gibco, cat. no. 15630-056)

- 1× GlutaMAX Supplement (Gibco, cat. no. 35050-038)

- 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, cat. no. 15140163)

- Store up to 1 month at 4°C

Blocking solution

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20

- 2% (v/v) donkey serum

- Prepare fresh before use

Differentiation medium

For base ENR medium :

- AdvDMEM+++ (see recipe)

- 1× B-27 Supplement (50×, serum free, Life Technologies, 17504-044)

- 20% (v/v) Rspo1-CM (see Support Protocol 2)

- 2% (v/v) Noggin conditioned medium (U-Protein Express, N002)

- 1.25 mM N -acetylcysteine (Sigma-Aldrich, A9165)

- 50 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF, Peprotech, AF-100-15)

- Store up to 1 month at 4°C

Before use, add differentiation components :

- 10 μM Notch inhibitor DAPT (Sigma-Aldrich, D5942)

- 0.1-1 μM MEK inhibitor PD0325901 (Sigma-Aldrich, PZ0162)

- 50 ng/ml BMP2 (Peprotech, 120-02C)

- 50 ng/ml BMP4 (Peprotech, 120-05ET)

See Table 1 for selection of appropriate medium. For ENR+Notchi, add DAPT to base medium. For ENR+MEKi+Notchi, add PD0325901 and DAPT to base medium. For ER+MEKi+Notchi+BMP2+BMP4, add all four components and omit Noggin CM. Additional differentiation components should be added fresh to the medium prior use.

DMEM++

- 1× DMEM + GlutaMAX-I (Gibco, cat. no. 31966-021)

- 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, cat. no. 15140163)

- 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. F7524)

- Store up to 1 month at 4°C

Expansion medium

- AdvDMEM+++ (see recipe)

- 1× B-27 Supplement (50×, serum free, Life Technologies, 17504-044)

- 50% (v/v) Wnt3A-CM (see Support Protocol 1) or 0.5 nM Wnt surrogate (U-Protein Express, N001)

- 20% (v/v) Rspo1-CM (see Support Protocol 2)

- 2% (v/v) Noggin conditioned medium (U-Protein Express, N002)

- 1.25 mM N -acetylcysteine (Sigma-Aldrich, A9165)

- 10 mM nicotinamide (Sigma-Aldrich, N0636)

- 10 μM p38 inhibitor SB202190 (Sigma-Aldrich, S7076)

- 50 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF, Peprotech, AF-100-15)

- 0.5 μM ALK5 inhibitor A83-01 (Tocris/Bio-Techne, 2939)

- 1 μM prostaglandin E2 (PGE2, Tocris/Bio-Techne, 2296)

- Store up to 1 month at 4°C

See Strategic Planning and Critical Parameters for discussions on the use of Wnt ligands. Omit Wnt ligands when culturing CRC-derived organoids.

Freezing medium, 2×

- 10 ml DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. D2650)

- 40 ml FBS (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. F7524)

- Store up to 1 month at 4°C

Permeabilization solution

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100

- 2% (v/v) donkey serum (Bio-Rad, C06SB)

- Prepare fresh before use

COMMENTARY

Background Information

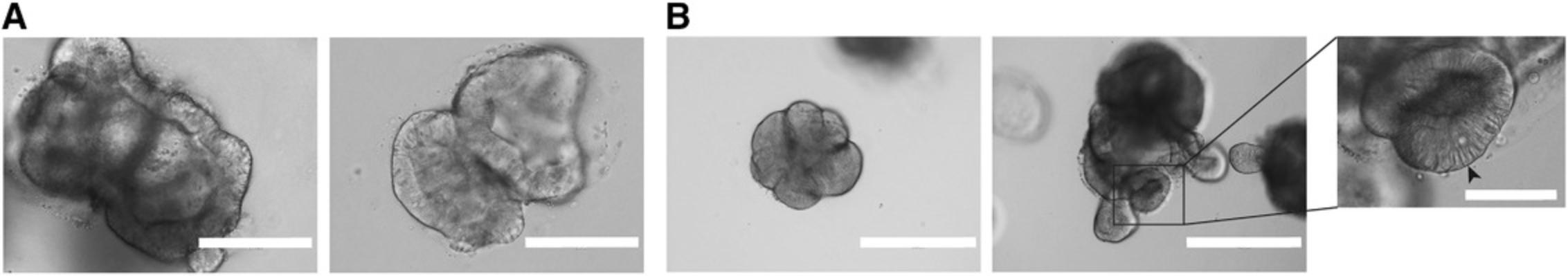

The initial development of ASC-derived organoids occurred hand-in-hand with knowledge obtained on the signaling pathways governing development of the adult intestinal epithelium. The intestinal crypt-villus (small intestine) or crypt (colon) structural units are hallmarks of adult stem cell functioning. Intestinal stem cells—marked by expression of the G-protein coupled receptor Lgr5—reside at the bottom of the crypts and are able to replenish the entire intestinal epithelium within a short turnover time of ∼5 days. Lgr5+ cells that reside at the bottom of the crypts actively divide, generating transit-amplifying cells. These cells proliferate and give rise to all functional epithelial cell types that carry out the essential intestinal functions (e.g., enterocytes, Paneth cells, enteroendocrine cells, goblet cells, tuft cells, and—at the Peyer's patches—M cells). The population dynamics of these cells are tightly governed by the action of four signaling pathways, namely Wnt, epidermal growth factor (EGF), Notch, and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) (Clevers, 2013).

ASC-derived intestinal organoids rely on the infinite ability of epithelial Lgr5+ stem cells to divide and repopulate the entire intestinal epithelium. The initial development of the technology was guided by knowledge on the niche factors that promote the stem cell state at the bottom of the crypt (Sato et al., 2009, 2011). By providing Wnt and EGF agonists and BMP inhibitors in the medium, these stem cells can be maintained and expanded in culture indefinitely. In the case of mouse small intestinal organoids, Paneth cells are a source of Wnt ligands that allow organoids to be cultured in the absence of an exogenous Wnt source. This inherently creates a local Wnt gradient around Paneth cells, giving rise to the characteristic budding structures of mouse small intestinal organoids. For human intestinal organoids, ectopic Wnt ligands need to be added to the medium, as Paneth cells do not produce as much Wnt as in the mouse. In turn, this leads to the characteristic cystic structures of human small intestine and colon organoids.

Critical Parameters and Troubleshooting

It is essential to establish organoid cultures from fresh biopsies after surgery and to avoid freezing the tissue. A substantial delay after surgery and freezing of the tissue can both result in failure to obtain organoids. Additionally, the quality (e.g., low proportion of epithelial cells, high proportion of necrotic cells) of the tissue biopsies influences the efficiency of organoid outgrowth.

One of the most critical parameters regarding the culture of human intestinal organoids is the source of Wnt pathway agonists and the level of Wnt pathway activation that they achieve. High levels of Wnt activation will result in cystic organoids that maintain most of their cells in a stem cell or transit-amplifying state, allowing indefinite expansion of the culture. On the other hand, if a suboptimal Wnt agonist source is used, stem cells will start to differentiate, leading to loss of the organoid culture after some passages. Wnt3A-CM is the most established source of Wnt agonist, and a protocol for its production is included here. However, batch-to-batch variability in Wnt activation activity mandates regular quality controls of this reagent. In order to overcome this problem, it is recommended to use a combination of different Wnt3A-CM batches, and to perform Wnt activity assays using a reporter cell line (ATCC, CRL-3249). Additionally, the recent development of synthetic Wnt agonists (Janda et al., 2017; Miao et al., 2020) has improved and facilitated the culture of human intestinal organoids, particularly when growing human colon organoids from single cells.

When using organoids for experiments, it is crucial to consider the cell type composition. Organoids cultured in expansion medium will predominantly consist of stem and transit-amplifying cells. These are useful in stem cell and cancer studies, but many experiments on healthy gut physiology require mature cell types. These can be obtained within 5 days using tailored differentiation media for all major mature cell types. It is crucial to validate differentiation success by quantitative real-time PCR for cell-type marker genes or antibody-based staining. Some of the most widely used markers for different intestinal epithelial cell types are: AXIN2 or OLFM4 for stem cells, FABP1 or Villin for enterocytes, CHGA for enteroendocrine cells, LYZ for Paneth cells, and MUC2 for goblet cells. Beyond the medium recipes provided here, other differentiation strategies can be applied (Beumer et al., 2020; Fujii et al., 2018) but are beyond the scope of this protocol.

Another matter of high importance is the effect of cell density on the ability to expand the organoid culture. The right seeding density (1) enables paracrine signaling support for organoid growth, (2) leaves space for organoids to grow, (3) avoids excessive consumption of media components, and (4) ensures adequate diffusion of growth factors to the core of BME domes. The seeding density has an especially crucial effect in the single-cell clonal expansion step. Seeding that is too sparse may greatly reduce outgrowth efficiency, whereas a high seeding density increases the risk of organoid fusion and thereby loss of clonality. This is especially relevant in experiments involving whole-genome sequencing, where the cost per genome is high. It is recommended to maintain organoids seeded at the density indicated in Basic Protocol 5 (Fig. 5). As mentioned previously, there is considerable inter-donor variability in organoid line density preference and tolerance. Some lines display expansion potential even at suboptimal density, whereas others tend to differentiate when plated too sparsely and lose viability when plated too densely.

Another important factor to consider is the addition of Rho kinase inhibitor in all steps at which organoids are dissociated to single cells, both during passage and once seeded. This will block anoikis, which otherwise occurs due to the loss of cell-cell contact.

Using low-attachment pipette tips and coating with FBS prior to pipetting prevents organoids from attaching to the pipette tip and thus subsequent material loss. This is particularly important when organoids are transferred in the first and last steps of whole-mount immunofluorescence staining (Basic Protocol 4), but can also be advisable when establishing organoid lines from limited material.

For a troubleshooting guide, see Table 3.

| Observation | Possible cause(s) | Suggested solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Organoids do not grow after isolation and establishment of line | Low quality; biopsy was incubated too long at 4°C or was frozen | Minimize time between biopsy and establishment of line |

| Biopsy was incubated too long in dissociation medium | Try to minimize the dissociation time | |

| Did not add RhoKi to the expansion medium | Add RhoKi to medium | |

| Organoids stop growing | Wnt3A-CM and Rspo1-CM batches do not provide optimal Wnt pathway activation | Test batches in organoids cultures before using in relevant cultures |

| Alternatively, test media using Wnt reporter cell lines | ||

| Organoid biomass lost at passage | Organoids trapped in foam generated during mechanical dissociation or in the filter of the Pasteur pipette |

Avoid foam formation by pipetting against tube wall; be careful not to let suspension reach the pipette filter when performing mechanical disruption |

| Organoids lost during staining | Organoids did not settle by gravity | Make sure that most of the organoids have settled before removing supernatant; a quick spin in a benchtop centrifuge (2 s) may help |

| Organoids adhered to plastic tip during last transfer | Use low-binding tips coated with FBS | |

| Organoids fail to differentiate (maintain cystic morphology) | Stem cell factors were not washed away properly before differentiation |

Starting with a fresh organoid culture in expansion medium, increase the number of 15-min wash cycles (up to three). Make sure to change medium 1 day after induction of differentiation. |

| Differentiation medium was not freshly prepared | Make fresh medium prior to experiment | |

| Differentiation components are missing | Check that all components were added to differentiation medium | |

| Excessively dark organoid morphology after differentiation | Cell death due to growth pathway inhibition/lack of expansion signals | Adjust inhibitor concentrations; assess other organoid lines for better differentiation capacity |

| Background after antibody staining | Residual BME attached to organoids after collection | Incubate longer in Cell Recovery Solution; use dispase as an alternative method |

| Antibody concentration not optimal | Optimize antibody concentration | |

| Permeabilization not optimal | Adjust permeabilization time | |

| Low single-cell outgrowth efficiency | Not enough Wnt activation | Optimize Wnt source and concentration |

| Seeding density too low | Optimize seeding density | |

| Trypsinization time was too long | Stop trypsinization after a maximum of 5 min | |

| Non-clonal organoid outgrowth (detected by WGS or imaging) | Single cells seeded at too high density, leading to organoid fusion | Seed cells at lower density and check daily under a microscope; make sure to pick only one organoid at a time |

Time Considerations

The amount of hands-on time dedicated to these techniques is not extensive, although organoid work is more dedicated and requires more attention than work with cell lines. Additionally, organoids grow considerably more slowly than standard cell lines. The time required to perform all these techniques depends on the number of lines being processed in parallel.

Typically, establishing one organoid line from a biopsy takes ∼3 hr, with 1.5 hr hands-on time. It normally takes an additional 2-4 weeks and two passages before enough biomass is generated for cryopreservation and experiments. Performing mechanical passage of a single organoid line could take ∼1 hr, with 15 min hands-on time. In general, the time required for organoids to expand after passage is 1 week, although donor-to-donor variability should be taken into consideration. Differentiation of organoids takes ∼30 min of hands-on time and 5 days of incubation. The staining protocol for organoid immunofluorescence usually takes 2 days if fixation is performed overnight. If fixation is performed for 2 hr at room temperature, it can be completed within 1 day. Establishing single-cell clonal organoid lines is a long process. In some cases, it can take 2 months before a fully clonal culture is established (one full well of a 12-well plate), or even longer depending on the donor. The hands-on time required for the initial step of single-cell culture establishment is ∼2 hr. Single-cell outgrowth to organoids can take 2 or 3 weeks depending on the organoid line. The time required to pick organoids depends highly on the number of clones to be picked. Picking and passing 24 clones from a single condition usually takes 30-60 min. Expansion of these clones in 48-well plates requires 1-2 weeks, after which another passage (1-2 weeks) will be required to obtain one full well of a 12-well plate per clonal culture. RNA extraction from organoids takes 30-60 min. DNA extraction from organoids takes ∼3 hr total time. The production of Wnt3A and Rspo1 conditioned medium takes 12 days for one batch. If more batches are produced in parallel, production time will increase to ∼20 days.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Bannier-Hélaouët for critical reading of the manuscript and comments. Development of this method was supported by CRUK grant OPTIMISTICC (C10674/A27140) (C.P.-M., J.P.), the Gravitation projects CancerGenomiCs.nl, and the Netherlands Organ-on-Chip Initiative (024.003.001) from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science of the government of the Netherlands (C.P.-M., J.P.), the Oncode Institute (partly financed by the Dutch Cancer Society), the European Research Council under ERC Advanced Grant Agreement no. 67013 (J.P., H.C.) and NETRF/Petersen Accelerator (J.B.).

Conflicts of Interest

H.C. is the inventor on several patents related to organoid technology; his full disclosure is given at https://www.uu.nl/staff/JCClevers/.

Author Contributions

Cayetano Pleguezuelos-Manzano : Methodology; writing-original draft; writing-review & editing. Jens Puschhof : Methodology; writing-original draft; writing-review & editing. Stieneke van den Brink : Methodology. Veerle Geurts : Methodology. Joep Beumer : Methodology. Hans Clevers : Funding acquisition; project administration; supervision.

Literature Cited

- Bar-Ephraim, Y. E., Kretzschmar, K., & Clevers, H. (2019). Organoids in immunological research. Nature Reviews Immunology , 20(5), 279–293. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0248-y.

- Beumer, J., Artegiani, B., Post, Y., Reimann, F., Gribble, F., Nguyen, T. N., … Clevers, H. (2018). Enteroendocrine cells switch hormone expression along the crypt-to-villus BMP signalling gradient. Nature Cell Biology , 20(8), 909–916. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0143-y.

- Beumer, J., Puschhof, J., Bauzá-Martinez, J., Martínez-Silgado, A., Elmentaite, R., James, K. R., … Clevers, H. (2020). High-resolution mRNA and secretome atlas of human enteroendocrine cells. Cell , 181(6), 1291–1306.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.036.

- Bigorgne, A. E., Farin, H. F., Lemoine, R., Mahlaoui, N., Lambert, N., Gil, M., … de Saint Basile, G. (2014). TTC7A mutations disrupt intestinal epithelial apicobasal polarity. Journal of Clinical Investigation , 124(1), 328–337. doi: 10.1172/JCI71471.

- Blokzijl, F., de Ligt, J., Jager, M., Sasselli, V., Roerink, S., Sasaki, N., … van Boxtel, R. (2016). Tissue-specific mutation accumulation in human adult stem cells during life. Nature , 538(7624), 260–264. doi: 10.1038/nature19768.

- Christensen, S., Van der Roest, B., Besselink, N., Janssen, R., Boymans, S., Martens, J. W. M., … Van Hoeck, A. (2019). 5-Fluorouracil treatment induces characteristic T>G mutations in human cancer. Nature Communications , 10(1), 4571. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12594-8.

- Clevers, H. (2013). The intestinal crypt, a prototype stem cell compartment. Cell , 154(2), 274–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.004.

- Clevers, H. (2016). Modeling development and disease with organoids. Cell , 165(7), 1586–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.082.

- Dekkers, J. F., Wiegerinck, C. L., de Jonge, H. R., Bronsveld, I., Janssens, H. M., de Winter-de Groot, K. M., … Beekman, J. M. (2013). A functional CFTR assay using primary cystic fibrosis intestinal organoids. Nature Medicine , 19(7), 939–945. doi: 10.1038/nm.3201.

- Dieterich, W., Neurath, M. F., & Zopf, Y. (2020). Intestinal ex vivo organoid culture reveals altered programmed crypt stem cells in patients with celiac disease. Scientific Reports , 10(1), 3535. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60521-5.

- Dijkstra, K. K., Cattaneo, C. M., Weeber, F., Chalabi, M., van de Haar, J., Fanchi, L. F., … Voest, E. E. (2018). Generation of tumor-reactive T cells by co-culture of peripheral blood lymphocytes and tumor organoids. Cell , 174(6), 1586–1598.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.009.

- Drost, J., & Clevers, H. (2018). Organoids in cancer research. Nature Reviews Cancer , 18(7), 407–418. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0007-6.

- Drost, J., van Jaarsveld, R. H., Ponsioen, B., Zimberlin, C., van Boxtel, R., Buijs, A., … Clevers, H. (2015). Sequential cancer mutations in cultured human intestinal stem cells. Nature , 521(7550), 43–47. doi: 10.1038/nature14415.

- Farin, H. F., Jordens, I., Mosa, M. H., Basak, O., Korving, J., Tauriello, D. V. F., … Clevers, H. (2016). Visualization of a short-range Wnt gradient in the intestinal stem-cell niche. Nature , 530(7590), 340–343. doi: 10.1038/nature16937.

- Freire, R., Ingano, L., Serena, G., Cetinbas, M., Anselmo, A., Sapone, A., … Senger, S. (2019). Human gut derived-organoids provide model to study gluten response and effects of microbiota-derived molecules in celiac disease. Scientific Reports , 9(1), 7029. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43426-w.

- Fujii, M., Clevers, H., & Sato, T. (2019). Modeling human digestive diseases with CRISPR-Cas9-modified organoids. Gastroenterology , 156(3), 562–576. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.11.048.

- Fujii, M., Matano, M., Nanki, K., & Sato, T. (2015). Efficient genetic engineering of human intestinal organoids using electroporation. Nature Protocols , 10(10), 1474–1485. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.088.

- Fujii, M., Matano, M., Toshimitsu, K., Takano, A., Mikami, Y., Nishikori, S., … Sato, T. (2018). Human intestinal organoids maintain self-renewal capacity and cellular diversity in niche-inspired culture condition. Cell Stem Cell , 23(6), 787–793.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.11.016.

- Geurts, M. H., de Poel, E., Amatngalim, G. D., Oka, R., Meijers, F. M., Kruisselbrink, E., … Clevers, H. (2020). CRISPR-based adenine editors correct nonsense mutations in a cystic fibrosis organoid biobank. Cell Stem Cell , 26(4), 503–510.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.01.019.

- Janda, C. Y., Dang, L. T., You, C., Chang, J., de Lau, W., Zhong, Z. A., … Garcia, K. C. (2017). Surrogate Wnt agonists that phenocopy canonical Wnt and β-catenin signalling. Nature , 545(7653), 234–237. doi: 10.1038/nature22306.

- Miao, Y., Ha, A., de Lau, W., Yuki, K., Santos, A. J. M., You, C., … Garcia, K. C. (2020). Next-generation surrogate Wnts support organoid growth and deconvolute Frizzled pleiotropy in vivo. Cell Stem Cell , 2020; S1934–5905(20), 30358–1. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.07.020.

- Nanki, K., Fujii, M., Shimokawa, M., Matano, M., Nishikori, S., Date, S., … Sato, T. (2020). Somatic inflammatory gene mutations in human ulcerative colitis epithelium. Nature , 577(7789), 254–259. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1844-5.

- Pleguezuelos-Manzano, C., Puschhof, J., Rosendahl Huber, A., van Hoeck, A., Wood, H. M., Nomburg, J., … Clevers, H. (2020). Mutational signature in colorectal cancer caused by genotoxic pks + E. coli. Nature , 580(7802), 269–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2080-8.

- Sato, T., Stange, D. E., Ferrante, M., Vries, R. G. J., van Es, J. H., van den Brink, S., … Clevers, H. (2011). Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett's epithelium. Gastroenterology , 141(5), 1762–1772. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050.

- Sato, T., Vries, R. G., Snippert, H. J., van de Wetering, M., Barker, N., Stange, D. E., … Clevers, H. (2009). Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature , 459(7244), 262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature07935.

- Schwank, G., Koo, B.-K., Sasselli, V., Dekkers, J. F., Heo, I., Demircan, T., … Clevers, H. (2013). Functional repair of CFTR by CRISPR/Cas9 in intestinal stem cell organoids of cystic fibrosis patients. Cell Stem Cell , 13(6), 653–658. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.002.

- van de Wetering, M., Francies, H. E., Francis, J. M., Bounova, G., Iorio, F., Pronk, A., … Clevers, H. (2015). Prospective derivation of a living organoid biobank of colorectal cancer patients. Cell , 161(4), 933–945. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.053.

- van Rijn, J. M., Ardy, R. C., Kuloğlu, Z., Härter, B., van Haaften-Visser, D. Y., van der Doef, H. P. J., … Boztug, K. (2018). Intestinal failure and aberrant lipid metabolism in patients with DGAT1 deficiency. Gastroenterology , 155(1), 130–143.e15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.040.

- Xu, Q., Wang, Y., Dabdoub, A., Smallwood, P. M., Williams, J., Woods, C., … Nathans, J. (2004). Vascular development in the retina and inner ear: Control by Norrin and Frizzled-4, a high-affinity ligand-receptor pair. Cell , 116(6), 883–895. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00216-8.

Citing Literature

Number of times cited according to CrossRef: 43

- Luming Wang, Danping Hu, Jinming Xu, Jian Hu, Yifei Wang, Complex in vitro model: A transformative model in drug development and precision medicine, Clinical and Translational Science, 10.1111/cts.13695, 17 , 2, (2024).

- Yu Zhang, Si‐Ming Lu, Jian‐Jian Zhuang, Li‐Guo Liang, Advances in gut–brain organ chips, Cell Proliferation, 10.1111/cpr.13724, 57 , 9, (2024).

- Qigu Yao, Sheng Cheng, Qiaoling Pan, Jiong Yu, Guoqiang Cao, Lanjuan Li, Hongcui Cao, Organoids: development and applications in disease models, drug discovery, precision medicine, and regenerative medicine, MedComm, 10.1002/mco2.735, 5 , 10, (2024).

- Brooke Wang, Lilianne Iglesias‐Ledon, Matthew Bishop, Anushka Chadha, Sara E. Rudolph, Brooke N. Longo, Dana M. Cairns, Ying Chen, David L. Kaplan, Impact of Micro‐ and Nano‐Plastics on Human Intestinal Organoid‐Derived Epithelium, Current Protocols, 10.1002/cpz1.1027, 4 , 4, (2024).

- Mathias Busch, Hugo Brouwer, Germaine Aalderink, Gerrit Bredeck, Angela A. M. Kämpfer, Roel P. F. Schins, Hans Bouwmeester, Investigating nanoplastics toxicity using advanced stem cell-based intestinal and lung in vitro models, Frontiers in Toxicology, 10.3389/ftox.2023.1112212, 5 , (2023).

- Sarit Cohen-Kedar, Efrat Shaham Barda, Keren Masha Rabinowitz, Danielle Keizer, Hanan Abu-Taha, Shoshana Schwartz, Kawsar Kaboub, Liran Baram, Eran Sadot, Ian White, Nir Wasserberg, Meirav Wolff-Bar, Adva Levy-Barda, Iris Dotan, Human intestinal epithelial cells can internalize luminal fungi via LC3-associated phagocytosis, Frontiers in Immunology, 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1142492, 14 , (2023).

- Shreya Gopalakrishnan, Ingunn Bakke, Marianne Doré Hansen, Helene Kolstad Skovdahl, Atle van Beelen Granlund, Arne K. Sandvik, Torunn Bruland, Comprehensive protocols for culturing and molecular biological analysis of IBD patient-derived colon epithelial organoids, Frontiers in Immunology, 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1097383, 14 , (2023).

- Xingfeng He, Yan Jiang, Long Zhang, Yaqi Li, Xiang Hu, Guoqiang Hua, Sanjun Cai, Shaobo Mo, Junjie Peng, Patient-derived organoids as a platform for drug screening in metastatic colorectal cancer, Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 10.3389/fbioe.2023.1190637, 11 , (2023).

- Xinyu Fan, Jiachen Shi, Ye Liu, Mengqiu Zhang, Min Lu, Ding Qu, Cannabidiol-Decorated Berberine-Loaded Microemulsions Improve IBS-D Therapy Through Ketogenic Diet-Induced Cannabidiol Receptors Overexpression, International Journal of Nanomedicine, 10.2147/IJN.S402871, Volume 18 , (2839-2853), (2023).

- Wouter A. G. Beenker, Jelmer Hoeksma, Marie Bannier-Hélaouët, Hans Clevers, Jeroen den Hertog, Paecilomycone Inhibits Quorum Sensing in Gram-Negative Bacteria, Microbiology Spectrum, 10.1128/spectrum.05097-22, 11 , 2, (2023).

- Ang Su, Miaomiao Yan, Suvarin Pavasutthipaisit, Kathrin D. Wicke, Guntram A. Grassl, Andreas Beineke, Felix Felmy, Sabine Schmidt, Karl-Heinz Esser, Paul Becher, Georg Herrler, Infection Studies with Airway Organoids from Carollia perspicillata Indicate That the Respiratory Epithelium Is Not a Barrier for Interspecies Transmission of Influenza Viruses , Microbiology Spectrum, 10.1128/spectrum.03098-22, 11 , 2, (2023).

- Thomas Däullary, Fabian Imdahl, Oliver Dietrich, Laura Hepp, Tobias Krammer, Christina Fey, Winfried Neuhaus, Marco Metzger, Jörg Vogel, Alexander J. Westermann, Antoine-Emmanuel Saliba, Daniela Zdzieblo, A primary cell-based in vitro model of the human small intestine reveals host olfactomedin 4 induction in response to Salmonella Typhimurium infection, Gut Microbes, 10.1080/19490976.2023.2186109, 15 , 1, (2023).

- Riley J. Morrow, Matthias Ernst, Ashleigh R. Poh, Longitudinal quantification of mouse gastric tumor organoid viability and growth using luminescence and microscopy, STAR Protocols, 10.1016/j.xpro.2023.102110, 4 , 1, (102110), (2023).

- Rebekkah Hammar, Mikael E. Sellin, Per Artursson, Epithelial and microbial determinants of colonic drug distribution, European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 10.1016/j.ejps.2023.106389, 183 , (106389), (2023).

- Laura Elomaa, Lorenz Gerbeth, Ahed Almalla, Nora Fribiczer, Assal Daneshgar, Peter Tang, Karl Hillebrandt, Sebastian Seiffert, Igor M. Sauer, Britta Siegmund, Marie Weinhart, Bioactive photocrosslinkable resin solely based on refined decellularized small intestine submucosa for vat photopolymerization of in vitro tissue mimics, Additive Manufacturing, 10.1016/j.addma.2023.103439, 64 , (103439), (2023).

- Mahnaz D. Damavandi, Yi Zhou, Simon J.A. Buczacki, Cancer Stem Cells, Encyclopedia of Cell Biology, 10.1016/B978-0-12-821618-7.00076-6, (114-123), (2023).

- Raehyun Kim, Advanced Organotypic In Vitro Model Systems for Host–Microbial Coculture, BioChip Journal, 10.1007/s13206-023-00103-5, (2023).

- Peter Flood, Naomi Hanrahan, Ken Nally, Silvia Melgar, Human intestinal organoids: Modeling gastrointestinal physiology and immunopathology — current applications and limitations, European Journal of Immunology, 10.1002/eji.202250248, 54 , 2, (2023).

- Adriana Mulero‐Russe, Andrés J. García, Engineered Synthetic Matrices for Human Intestinal Organoid Culture and Therapeutic Delivery, Advanced Materials, 10.1002/adma.202307678, 36 , 9, (2023).

- Julia Y. Co, Jessica A. Klein, Serah Kang, Kimberly A. Homan, Toward Inclusivity in Preclinical Drug Development: A Proposition to Start with Intestinal Organoids, Advanced Biology, 10.1002/adbi.202200333, 7 , 12, (2023).

- Intan Rosalina Suhito, Tae-Hyung Kim, Recent advances and challenges in organoid-on-a-chip technology, Organoid, 10.51335/organoid.2022.2.e4, 2 , (e4), (2022).

- Matteo Centonze, Erwin J. W. Berenschot, Simona Serrati, Arturo Susarrey-Arce, Silke Krol, The Fast Track for Intestinal Tumor Cell Differentiation and In Vitro Intestinal Models by Inorganic Topographic Surfaces, Pharmaceutics, 10.3390/pharmaceutics14010218, 14 , 1, (218), (2022).

- Sara Furbo, Paulo César Martins Urbano, Hans Henrik Raskov, Jesper Thorvald Troelsen, Anne-Marie Kanstrup Fiehn, Ismail Gögenur, Use of Patient-Derived Organoids as a Treatment Selection Model for Colorectal Cancer: A Narrative Review, Cancers, 10.3390/cancers14041069, 14 , 4, (1069), (2022).

- Gregorio Di Franco, Alice Usai, Margherita Piccardi, Perla Cateni, Matteo Palmeri, Luca Emanuele Pollina, Raffaele Gaeta, Federica Marmorino, Chiara Cremolini, Luciana Dente, Alessandro Massolo, Vittoria Raffa, Luca Morelli, Zebrafish Patient-Derived Xenograft Model to Predict Treatment Outcomes of Colorectal Cancer Patients, Biomedicines, 10.3390/biomedicines10071474, 10 , 7, (1474), (2022).

- Yu-Yin Shih, Chun-Hung Lin, Kuan-Ting Liu, Kai-Wen Kan, Hsien-Ya Lin, Ming-You Shie, Yi-Wen Chen, Supplement of iron abrogates SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus infection in a 3D model of vascularized organoids, 2022 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering (BIBE), 10.1109/BIBE55377.2022.00036, (134-136), (2022).

- Wadzanai P. Mboko, Preeti Chhabra, Marta Diez Valcarce, Veronica Costantini, Jan Vinjé, Advances in understanding of the innate immune response to human norovirus infection using organoid models, Journal of General Virology, 10.1099/jgv.0.001720, 103 , 1, (2022).

- Lyan Abdul, Jocelyn Xu, Alexander Sotra, Abbas Chaudary, Jerry Gao, Shravanthi Rajasekar, Nicky Anvari, Hamidreza Mahyar, Boyang Zhang, D-CryptO: deep learning-based analysis of colon organoid morphology from brightfield images, Lab on a Chip, 10.1039/D2LC00596D, 22 , 21, (4118-4128), (2022).

- Laween Meran, Lucinda Tullie, Simon Eaton, Paolo De Coppi, Vivian S. W. Li, Bioengineering human intestinal mucosal grafts using patient-derived organoids, fibroblasts and scaffolds, Nature Protocols, 10.1038/s41596-022-00751-1, 18 , 1, (108-135), (2022).

- Joseph L. Regan, Protocol for isolation and functional validation of label-retaining quiescent colorectal cancer stem cells from patient-derived organoids for RNA-seq, STAR Protocols, 10.1016/j.xpro.2022.101225, 3 , 1, (101225), (2022).

- Gui-Wei He, Lin Lin, Jeff DeMartino, Xuan Zheng, Nadzeya Staliarova, Talya Dayton, Harry Begthel, Willine J. van de Wetering, Eduard Bodewes, Jeroen van Zon, Sander Tans, Carmen Lopez-Iglesias, Peter J. Peters, Wei Wu, Daniel Kotlarz, Christoph Klein, Thanasis Margaritis, Frank Holstege, Hans Clevers, Optimized human intestinal organoid model reveals interleukin-22-dependency of paneth cell formation, Cell Stem Cell, 10.1016/j.stem.2022.08.002, 29 , 9, (1333-1345.e6), (2022).

- Shuxin Zhang, Shujuan Du, Yuyan Wang, Yuping Jia, Fang Wei, Daizhou Zhang, Qiliang Cai, Caixia Zhu, Rapid establishment of murine gastrointestinal organoids using mechanical isolation method, Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.03.151, 608 , (30-38), (2022).

- Joseph L. Regan, Immunofluorescence staining of colorectal cancer patient-derived organoids, Methods in Stem Cell Biology - Part B, 10.1016/bs.mcb.2022.04.008, (163-171), (2022).

- Sifan Ai, Hui Li, Hao Zheng, Jinming Liu, Jie Gao, Jianfeng Liu, Quan Chen, Zhimou Yang, A SupraGel for efficient production of cell spheroids一种高效生产细胞球的超分子水凝胶, Science China Materials, 10.1007/s40843-021-1951-x, 65 , 6, (1655-1661), (2022).

- Janine Häfliger, Yasser Morsy, Michael Scharl, Marcin Wawrzyniak, From Patient Material to New Discoveries: a Methodological Review and Guide for Intestinal Stem Cell Researchers, Stem Cell Reviews and Reports, 10.1007/s12015-021-10307-7, 18 , 4, (1309-1321), (2022).

- Bruna Costa, Marta F. Estrada, Mariana Tavares Barroso, Rita Fior, Zebrafish Patient‐Derived Avatars from Digestive Cancers for Anti‐cancer Therapy Screening, Current Protocols, 10.1002/cpz1.415, 2 , 4, (2022).

- Margarita Jimenez-Palomares, Alba Cristobal, Mª Carmen Duran Ruiz, Organoids Models for the Study of Cell-Cell Interactions, Cell Interaction - Molecular and Immunological Basis for Disease Management, 10.5772/intechopen.94562, (2021).

- Alexane Ollivier, Maxime M. Mahe, Géraldine Guasch, Modeling Gastrointestinal Diseases Using Organoids to Understand Healing and Regenerative Processes, Cells, 10.3390/cells10061331, 10 , 6, (1331), (2021).

- Erika Durinikova, Kristi Buzo, Sabrina Arena, Preclinical models as patients’ avatars for precision medicine in colorectal cancer: past and future challenges, Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research, 10.1186/s13046-021-01981-z, 40 , 1, (2021).

- Jens Puschhof, Cayetano Pleguezuelos-Manzano, Adriana Martinez-Silgado, Ninouk Akkerman, Aurelia Saftien, Charelle Boot, Amy de Waal, Joep Beumer, Devanjali Dutta, Inha Heo, Hans Clevers, Intestinal organoid cocultures with microbes, Nature Protocols, 10.1038/s41596-021-00589-z, 16 , 10, (4633-4649), (2021).

- Francesca Perrone, Matthias Zilbauer, Biobanking of human gut organoids for translational research, Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 10.1038/s12276-021-00606-x, 53 , 10, (1451-1458), (2021).

- Ibrahim M. Sayed, Amer Ali Abd El-Hafeez, Priti P. Maity, Soumita Das, Pradipta Ghosh, Modeling colorectal cancers using multidimensional organoids, Novel Approaches to Colorectal Cancer, 10.1016/bs.acr.2021.02.005, (345-383), (2021).

- Yuka Matsumoto, Hiroyuki Koga, Mirei Takahashi, Kazuto Suda, Takanori Ochi, Shogo Seo, Go Miyano, Yuichiro Miyake, Hideaki Nakajima, Shiho Yoshida, Takafumi Mikami, Tadaharu Okazaki, Nobutaka Hattori, Atsuyuki Yamataka, Tetsuya Nakamura, Defined serum-free culture of human infant small intestinal organoids with predetermined doses of Wnt3a and R-spondin1 from surgical specimens, Pediatric Surgery International, 10.1007/s00383-021-04957-4, 37 , 11, (1543-1554), (2021).

- Aafke W. F. Janssen, Loes P. M. Duivenvoorde, Deborah Rijkers, Rosalie Nijssen, Ad A. C. M. Peijnenburg, Meike van der Zande, Jochem Louisse, Cytochrome P450 expression, induction and activity in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived intestinal organoids and comparison with primary human intestinal epithelial cells and Caco-2 cells, Archives of Toxicology, 10.1007/s00204-020-02953-6, 95 , 3, (907-922), (2020).