Automated Laboratory Growth Assessment and Maintenance of Azotobacter vinelandii

Brooke M. Carruthers, Brooke M. Carruthers, Amanda K. Garcia, Amanda K. Garcia, Alex Rivier, Alex Rivier, Betul Kacar, Betul Kacar

Abstract

Azotobacter vinelandii (A. vinelandii) is a commonly used model organism for the study of aerobic respiration, the bacterial production of several industrially relevant compounds, and, perhaps most significantly, the genetics and biochemistry of biological nitrogen fixation. Laboratory growth assessments of A. vinelandii are useful for evaluating the impact of environmental and genetic modifications on physiological properties, including diazotrophy. However, researchers typically rely on manual growth methods that are oftentimes laborious and inefficient. We present a protocol for the automated growth assessment of A. vinelandii on a microplate reader, particularly well-suited for studies of diazotrophic growth. We discuss common pitfalls and strategies for protocol optimization, and demonstrate the protocol's application toward growth evaluation of strains carrying modifications to nitrogen-fixation genes. © 2021 The Authors.

This article was corrected on 13 January 2022 and 26 July 2022. See the end of the full text for details.

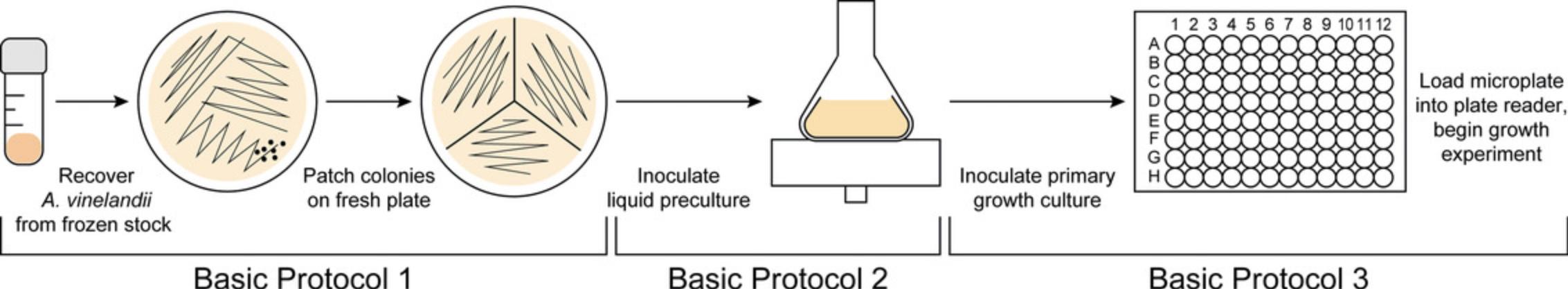

Basic Protocol 1 : Preparation of A. vinelandii plate cultures from frozen stock

Basic Protocol 2 : Preparation of A . vinelandii liquid precultures

Basic Protocol 3 : Automated growth rate experiment of A. vinelandii on a microplate reader

INTRODUCTION

Azotobacter vinelandii (A. vinelandii), a Gram-negative, obligately aerobic, diazotrophic Gamma proteobacterium, has been an important model organism since its discovery more than a century ago (Lipman, 1903). One of the most significant contributions of the A. vinelandii model has been toward understanding the evolution, genetics, and biochemistry of nitrogenase-catalyzed nitrogen fixation (Dos Santos, 2019; Hoffman, Lukoyanov, Yang, Dean, & Seefeldt, 2014; Hu, Fay, Lee, Wiig, & Ribbe, 2010; Noar & Bruno-Barcena, 2018). A. vinelandii growth assays are utilized to evaluate the physiological impact of genomic modifications and varied environmental conditions on diazotrophic growth (Arragain et al., 2017; McRose, Baars, Morel, & Kraepiel, 2017; Mus, Tseng, Dixon, & Peters, 2017; Plunkett, Knutson, & Barney, 2020). However, manual assays of A. vinelandii , which have a doubling time of ∼2 to 4 hr under normal diazotrophic conditions (Page & von Tigerstrom, 1979), are typically laborious and time consuming. Moreover, automated growth methods that are common for other model bacteria such as Escherichia coli (Hall, Acar, Nandipati, & Barlow, 2014; Kurokawa & Ying, 2017; Wong, Mancuso, Kiriakov, Bashor, & Khalil, 2018) are not yet reported for A. vinelandii.

Addressing this gap, here we present a laboratory protocol for high-throughput A. vinelandii growth evaluation on a microplate reader, which can provide precise measurements of growth rates that are comparable or preferable to those obtained by manual spectrophotometer measurements (Hall et al., 2014). This protocol details A. vinelandii growth assessments beginning with recovery of bacterial stocks and preparation of inoculum for liquid cultures, and provides instruction for culture maintenance and automated optical density measurements on a standard microplate reader (Fig. 1). This approach is appropriate for the efficient investigation of growth rates for wild-type and engineered A. vinelandii strains, as well as for their evaluation under varying physical and nutritional environmental conditions of interest.

CAUTION: Azotobacter vinelandii is a Biosafety Level 1 (BSL-1) organism. Such organisms are not known to consistently cause disease in healthy adult humans and are of minimal potential hazard to laboratory personnel and the environment. Standard microbiological practices should be followed when working with these organisms. See Burnett, Lunn, & Coico, 2009 for more information.

STRATEGIC PLANNING

Strain Acquisition

The laboratory wild-type variant of A. vinelandii is the non-alginate-producing OP strain (Burk & Lineweaver, 1930; Dos Santos, 2019), a spontaneous mutant of the alginate-producing strain isolated by (Lipman, 1903). Alternative designations of the OP strain include the UW (University of Wisconsin-Madison) and CA (North Carolina State University) strains. Nevertheless, several non-wild-type A. vinelandii variants including alginate-producing strains are commonly used for different applications. Some of these variants are available from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), including the high-frequency-transforming DJ strain, the genome of which has been fully sequenced (Setubal et al., 2009) (ATCC BAA-1303). Due to the availability of genomic sequence information and tractability for genetic manipulation studies, the DJ strain was selected for development of this protocol, generously provided by Dennis Dean (Virginia Tech). However, other strains may be used depending on the desired application.

Optimization of growth conditions

Microplate readers with temperature control and continuous shaking capabilities can be used for A. vinelandii maintenance and growth rate determination. Standard A. vinelandii cultures are typically grown in flasks and shaken from 100 to 300 rpm at 30°C (Arragain et al., 2017; Dos Santos, 2019; McRose et al., 2017; Mus et al., 2017). However, these growth conditions can be further optimized or varied depending on experimental design and instrument capabilities.

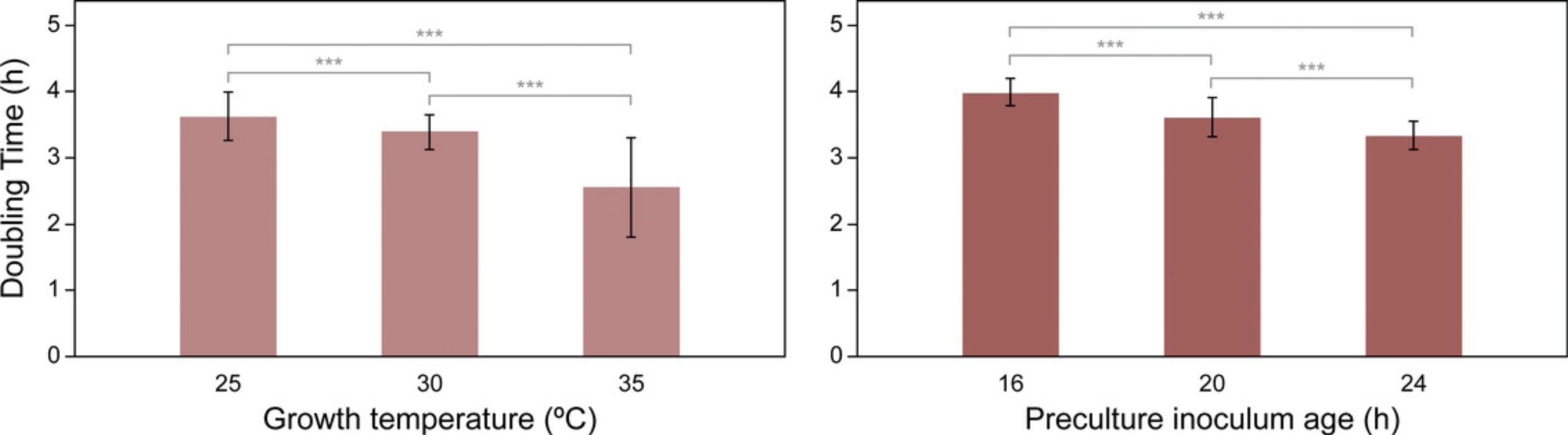

Factors that may impact growth and should, thus, be considered when designing the experiment include temperature, shaking speed, culture volume, and inoculum preparation. As an example, we assessed A. vinelandii growth as a function of variation in temperature and preculture inoculum age (Fig. 2). We found that both temperature and preculture inoculum age led to significant (p < 0.05) differences in doubling times, with both increasing temperature and increasing inoculum age resulting in faster doubling times across the measured range. It is recommended that the user similarly optimize for key growth conditions with their equipment. Culture volume in particular may have a significant effect on growth rate by altering the amount of headspace in the well and culture movement during shaking. Culture volume should be optimized after shaking speed, as different volumes may be optimal at different shaking speeds. Additional care should be given to ensure consistency across the plate wells, which can be accomplished by using a lid or gas-permeable membrane to minimize evaporation and cross-contamination. The use of these items may result in slower A. vinelandii growth rates as compared to flask-grown cultures due to impeded aeration but should not preclude comparisons across samples grown in similar conditions.

Reproducibility

All qualitative and quantitative experimental parameters, particularly those used to operate the microplate reader, should be reported to facilitate future reproducibility (Chavez, Ho, & Tan, 2017). Multiple repeat measurements can be made simultaneously across aliquots of the same samples in a single microplate, but experimental replicates should be performed on different inoculations and days to account for variability of the bacterial stock and day-to-day instrument performance.

Data analysis

When analyzing growth measurements from high-throughput procedures, it is recommended to use reproducible and efficient data analysis methods. Several free software packages are available for analysis of growth data. The R package GrowthCurver (Sprouffske & Wagner, 2016) was used for analyses reported in this protocol. GrowthCurver calculates growth parameters by fitting data to a standard form of the logistic equation and is well suited for handling high-throughput growth measurements.

Basic Protocol 1: PREPARATION OF A. VINELANDII PLATE CULTURES FROM FROZEN STOCKS

A growth rate experiment of A. vinelandii begins with strain recovery from frozen stocks. A. vinelandii stocks are typically kept in a 7% DMSO storage buffer and stored at –80°C. Frozen cells can then be directly streaked on solid medium to prepare isogenic plate cultures for subsequent growth rate assessments.

A. vinelandii is generally grown in Burk's medium (B medium; see Reagents and Solutions), which may be supplemented with a nitrogen source (BN medium), antibiotics, or modified trace metals as desired. This protocol describes recovery on BN plates (rather than B plates) so that cells can be grown regardless of the diazotrophic capabilities of the strain, which can later be assessed during the growth rate experiment. If needed, recovery can also be accomplished with BN plates supplemented with antibiotics.

Materials

-

A. vinelandii (ATCC BAA-1303) frozen stock on ice

-

BN solid medium plates (see recipe)

-

Bunsen burner

-

Biosafety cabinet (optional)

-

Inoculation loops or needles (sterile)

-

30°C incubator

-

4°C refrigerator (as needed)

-

−80°C freezer

1.Use a sterile inoculation loop or needle to streak a small amount (enough to be just visible on the tip of the inoculation tool) of frozen cells onto a BN plate. Streak for isolation, and immediately return frozen stock to –80°C.

2.Incubate plates for 2 to 3 days at 30°C.

3.Use a sterile inoculation loop or needle to patch one full-sized colony onto a fresh BN plate.

4.Incubate plates for 2 to 3 days at 30°C.

Basic Protocol 2: PREPARATION OF A. VINELANDII LIQUID PRECULTURES

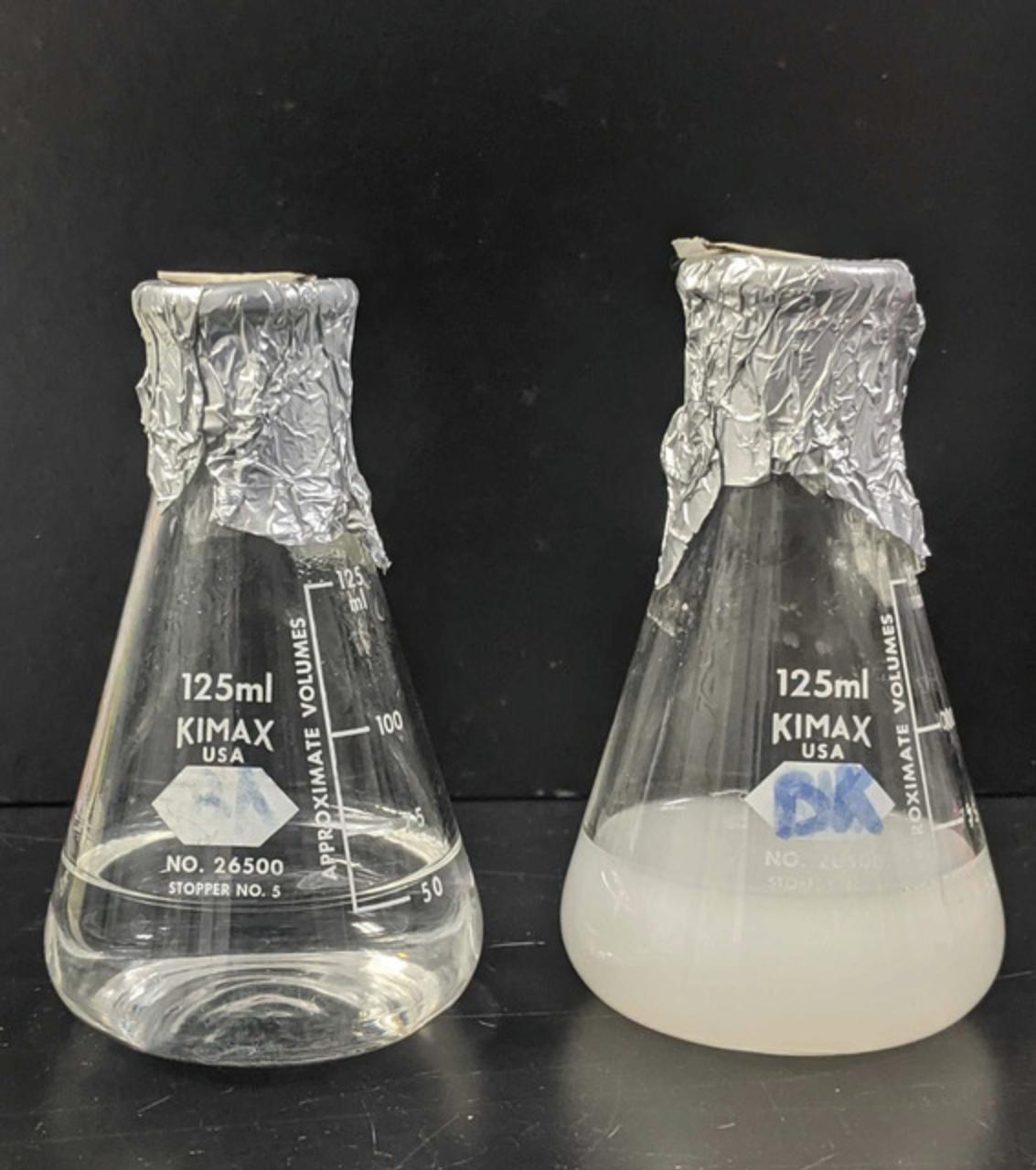

Preparation of A. vinelandii liquid precultures prior to the growth rate experiment is necessary to produce inocula that are in a consistent physiological state across different strains and replicates. The age of the preculture at the time of inoculation into the primary growth culture can be optimized as needed. A saturated preculture tends to provide a longer and more easily detectable lag phase for curve fitting in downstream growth rate analyses. Furthermore, it minimizes the volume of preculture needed to inoculate the primary culture, which can introduce undesirable residual medium additions (such as supplemental nitrogen) from the preculture that result in a variable lag phase.

Materials

-

Isogenic A. vinelandii plate culture (from Basic Protocol 1)

-

BN medium (sterile; see recipe)

-

Glass 125-ml flasks capped with aluminum foil (sterile)

-

Serological pipets (sterile)

-

Inoculation loops or needles (sterile)

-

Vortex (optional)

-

30°C shaking incubator

1.Using a serological pipet, transfer 50 ml sterile, room temperature BN liquid medium into a 125-ml glass flask.

2.Use a sterile inoculation loop or needle to inoculate the BN liquid medium with A. vinelandii cells (full ∼1 to 5 μl loop). Let cells sit in liquid medium for ∼5 min, then swirl or vortex to completely resuspend.

3.Shake liquid culture for 24 hr at 30°C and 300 rpm.

Basic Protocol 3: AUTOMATED GROWTH RATE EXPERIMENT OF A. VINELANDII ON A MICROPLATE READER

This protocol focuses on the automated assessment of A. vinelandii diazotrophic growth in B (nitrogen-free) medium on a microplate reader. Liquid precultures grown in BN (Basic Protocol 2) are used to inoculate B medium to a desired starting optical density at 600 nm (OD600) for the growth rate experiment. In B medium, A. vinelandii quickly use up any residual ammonia from the preculture and begin expressing nitrogenase genes for nitrogen fixation. Detected growth is, thus, directly related to the strain's ability to express nitrogenase and grow diazotrophically. Experiments targeting other aspects of A. vinelandii physiology can be designed by modifying the preculture and primary culture medium with, for example, antibiotics or different concentrations of trace metals. Over the course of the growth rate experiment, the microplate reader can provide automated temperature control, shaking, and optical density measurements, all parameters which can be varied to test different growth conditions as permitted by the instrument capabilities.

Materials

-

A. vinelandii saturated preculture in BN medium (from Basic Protocol 2)

-

B medium (sterile; see recipe)

-

Glass flasks (sterile)

-

Serological pipets (sterile)

-

96-well microplates, clear, flat-bottomed (sterile) (Greiner Bio-One, cat. no. 655161)

-

Multichannel pipette

-

50-ml pipetting reservoirs (sterile)

-

Microplate lid (optional) (Greiner Bio-One, cat. no. 656171)

-

Gas-permeable microplate membrane (optional) (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. Z380059)

-

Microplate reader (Tecan Spark, cat. no. 30086376)

Prepare the primary growth culture

1.In a sterile glass flask (or other small vessel), prepare a 1:10 dilution of the A. vinelandii preculture in sterile B medium (e.g., 1 ml preculture in 9 ml B medium). Swirl gently to mix.

2.Transfer 125 μl of the diluted A. vinelandii preculture to a single well of a 96-well microplate. In addition, transfer 125 μl of sterile B medium to a separate well to serve as blank reference for the absorbance reading.

3.Measure the OD600 of the diluted preculture on the microplate reader, taking a single absorbance reading of the wells.

4.Based on the initial OD600 value of the diluted preculture, in a glass flask (or other appropriate vessel), inoculate B medium to obtain a final OD600 of ∼0.05 for the main growth culture. Swirl gently to mix.

Prepare microplate and perform growth rate experiment

5.Pour the primary growth culture into a reagent reservoir. Use a multichannel pipette to aliquot 125 μl across the wells of a microplate. Reserve at least one well to fill with 125 μl of B medium to serve as a blank reference for the experiment.

6.Use a lid or gas-permeable membrane to cover the wells of the microplate.

7.Insert the prepared microplate into the reader, set the instrument parameters, and start the growth experiment program.

1.Temperature (typically 30°C) 2.Shaking speed (typically ∼300 rpm) 3.Shaking mode (e.g., orbital) 4.Measurement interval (e.g., once per hour) 5.Experiment duration (see below) 6.Absorbance wavelength (typically 600 nm) and other measurement parameters

(e.g., single vs. multiple reads per well)

These parameters should be optimized beforehand (see Strategic Planning). A. vinelandii cultures grown on a microplate reader typically reach saturation after ∼48 hr. However, growth should be monitored longer (up to ∼72 hr) to ensure sufficient duration of the stationary phase for curve fitting in downstream analyses. The appropriate experimental duration for mutant strains or modified growth conditions may vary.

8.Save the growth experiment file and export for subsequent data analysis (see Strategic Planning and Fig. 4).

REAGENTS AND SOLUTIONS

Ammonium acetate solution, 100×

- Weigh 10 g ammonium acetate (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. A7262) into a 250-ml beaker

- Dissolve in dH2O up to 100 ml

- Filter sterilize (0.2 μm) 10-ml aliquots

- Store up to 1 year at room temperature

Burk's (B) medium/Burk's nitrogen-supplemented (BN) medium

- Dilute 5 ml sterile 10× salts solution into 45 ml sterile 1× phosphate buffer

- Optional for BN medium: Add 0.5 ml sterile 100× ammonium acetate solution

- Prepare fresh

Burk's (B) medium/Burk's nitrogen-supplemented (BN) medium, solid

- Weigh 8 g agar (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. A1296) into a 1-L bottle

- Dilute 4.5 ml 100× phosphate buffer into 445 ml dH2O

- Sterilize by autoclaving for 20 min at 121°C

- Cool to 55°C in a water bath

- Add 50 ml sterile 10× salts solution

- Optional for BN medium: Add 5 ml sterile 100× ammonium acetate solution

- Pour ∼25 ml into plates and cool

- Store plates in sealed sleeve up to several months at 4°C

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) storage buffer, 7%

- Dilute 7 ml DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 472301) into 90 ml sterile 1× phosphate buffer

- Mix well (do not filter sterilize)

- Divide into 1-ml aliquots into cryovials for strain storage

- Store up to 2 days at 4°C

Phosphate buffer, 100×

- Weigh 22 g KH2PO4 (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. P5379) and 88 g K2HPO4 (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. P8281) into a 1-L bottle

- Dissolve in dH2O up to 1 L

- Store up to 1 year at room temperature

Phosphate buffer, 1×

- Dilute 5 ml 100× phosphate buffer into 495 ml dH2O

- Sterilize by autoclaving for 20 min at 121°C

- Store up to 1 year at room temperature

Salts solution, 10×

- Add 100 g sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. S0389), 1 g MgSO4·7H2O (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. M2773), 0.45 g CaCl2·2H2O (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 223506), 0.5 ml of 10 mM Na2MoO4·2H2O (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 331058), and 25 mg FeSO4·7H2O (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. F8633) to 1-L bottle

- Dissolve in dH2O up to 500 ml

- Sterilize by autoclaving for 20 min at 121°C

- Store up to 1 year at room temperature

COMMENTARY

Background Information

Since its discovery more than 100 years ago (Lipman, 1903), A. vinelandii has served a variety of scientific and industrial applications. These include the study of aerobic respiration (Poole & Hill, 1997), hydrogen uptake and production (Kow & Burris, 1984; Noar, Loveless, Navarro-Herrero, Olson, & Bruno-Barcena, 2015), polymer production (Clementi, 1997; Galindo, Pena, Nunez, Segura, & Espin, 2007), and, importantly, the genetics and biochemistry of nitrogenase-catalyzed nitrogen fixation (Dos Santos, 2019; Hoffman et al., 2014; Noar & Bruno-Barcena, 2018). Due to the challenge of heterologous expression of functional nitrogenases A. vinelandii has been used for their expression, purification, and biochemical characterization (Hoffman et al., 2014; Lee, Ribbe, & Hu, 2019; Solomon et al., 2020). Furthermore, A. vinelandii , which exhibits diauxic metabolism (George, Costenbader, & Melton, 1985) and grows in a wide range of oxygen levels (Dingler, Kuhla, Wassink, & Oelze, 1988), is an important model for studying nitrogen fixation in diverse environments. Recently, this organism has been involved in a renewed interest in biofertilizers (Ambrosio, Ortiz-Marquez, & Curatti, 2017; Khdhiri et al., 2017; Nosheen et al., 2016; Olivares, Bedmar, & Sanjuan, 2013), and the examination and manipulation of nitrogenase genes in A. vinelandii have informed efforts to engineer nitrogen fixation in cereal crops to improve agricultural yields (Buren & Rubio, 2018; Jimenez-Vicente & Dean, 2017). Finally, A. vinelandii serves as a promising microbial background for the insertion of reconstructed ancestral nitrogenase genes, which can reveal phenotypic insights into early evolutionary states of nitrogen fixation (Garcia & Kacar, 2019).

The aerobic A. vinelandii is an appealing model organism for laboratory work due to its relative ease of maintenance, genetic tractability, and non-pathogenicity (Biosafety Level 1), as compared with other pathogenic or anaerobically cultivated diazotroph models (e.g., Clostridium pasteurianum , Klebsiella pneumoniae , Rhodopseudomonas palustris). A. vinelandii can be maintained in ambient, benchtop conditions, though growth is typically optimized and standardized in an incubator. Natural competency for transformation in A. vinelandii can be induced via metal starvation and visually confirmed due to the associated production of fluorescent green siderophores (McRose et al., 2017). This characteristic makes it a highly suitable organism for genetic manipulation, as reviewed in (Dos Santos, 2019). Growth rate assessments of genetically modified A. vinelandii can, therefore, reveal the physiological contributions of nitrogenase and nitrogenase-related genes (Arragain et al., 2017; Garcia, McShea, Kolaczkowski, & Kaçar, 2020; McRose et al., 2017; Mus, Colman, Peters, & Boyd, 2019; Plunkett et al., 2020).

Critical Parameters and Troubleshooting

It is important to optimize conditions for A. vinelandii growth on a microplate reader prior to growth rate assessment to ensure consistency and reproducibility across biological and technical replicates (see Strategic Planning). Growth conditions that should be considered include temperature, shaking speed, culture volume, and inoculum preparation.

A common problem encountered during growth rate assessment on a microplate reader (Basic Protocol 3) is well evaporation over the approximately 48 to 72 hr needed for A. vinelandii cultures to reach saturation. Evaporation can be minimized by use of a lid or gas-permeable membrane. However, significant evaporation can still occur at plate edges when using a lid (Chavez et al., 2017), and improper application of the membrane can result in variable growth rates across the plate. Since such variability is challenging to eliminate entirely, it is important to include several technical replicates across the plate and avoid measuring wells at the plate edges when using a lid.

Time Considerations

The initial recovery of Azotobacter strains (Basic Protocol 1) and preparation of isogenic plate cultures (Basic Protocol 2) takes approximately 6 days. Preculture preparation (Basic Protocol 2) takes approximately 24 hr. This time can be optimized but should be made consistent across replicates. Each microplate reader growth experiment takes approximately 48 to 72 hr, though this time may vary depending on the tested strain and growth conditions. The experiment should be maintained until cultures reach saturation to ensure reliable curve-fitting during subsequent growth data analysis.

Understanding results

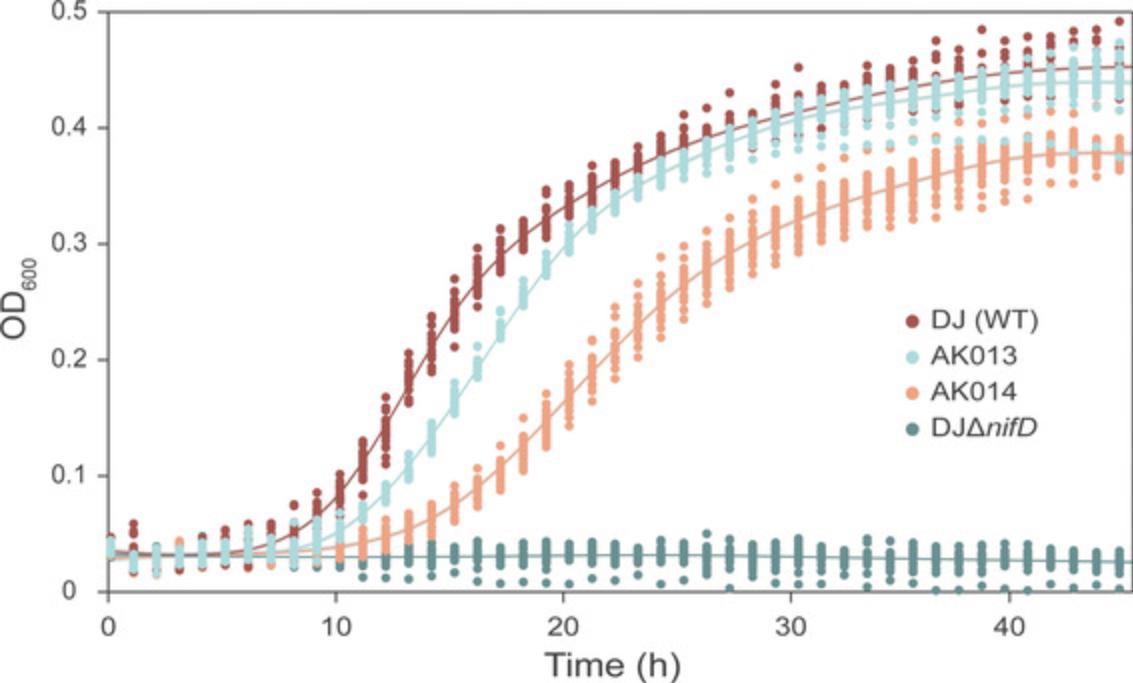

This protocol can also be used to compare the growth rates and characteristics of different wild-type and engineered A. vinelandii strains, as well as different physical and nutritional growth conditions. To provide an example of anticipated results for the protocol described here, we conducted diazotrophic growth rate experiments on wild-type Azotobacter vinelandii DJ and three strains harboring modifications to the nitrogenase nifD gene. The nifD gene encodes the active site-containing subunit of the nitrogenase enzyme. Modifications to this gene are expected to influence nitrogenase N2-reduction and, thus, the ability of A. vinelandii to grow diazotrophically. The modified strains include “AK013” and “AK014”, which have 93% and 81% nifD DNA identity to nifD of the wild-type DJ strain, respectively, and a DJΔ nifD deletion strain.

Figure 4 shows growth curves for each A. vinelandii strain, and Table 1 reports mean doubling times calculated with the R package GrowthCurver (Sprouffske & Wagner, 2016). We did not detect diazotrophic growth for DJΔ nifD. For Trials 1 and 2, AK014 grew slower than both DJ and AK013 (p < 0.05; calculated from a post-hoc Tukey's HSD test following a one-way ANOVA), but no difference in doubling times was found for DJ and AK013. However, for Trial 3, DJ grew significantly slower than both AK013 and AK014. This result highlights the need to repeat growth experiments on multiple days to account for day-to-day instrument variability. This automated protocol for evaluating diazotrophic growth differences across different A. vinelandii strains can be adapted for a variety of additional applications.

| Mean doubling time ± 1σ (hr) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | DJ (wild-type) | AK013 | AK014 |

| Trial 1 | 2.95 ± 0.13 | 2.83 ± 0.11 | 3.62 ± 0.20 |

| Trial 2 | 2.88 ± 0.17 | 2.74 ± 0.11 | 3.47 ± 0.30 |

| Trial 3 | 4.63 ± 0.18 | 3.23 ± 0.10 | 4.36 ± 0.24 |

Acknowledgments

We thank Dennis Dean and Valerie Cash for providing the A. vinelandii DJ and DJΔ nifD strains, as well as for support and helpful discussions. We acknowledge funding from the NASA Early Career Faculty (ECF) Award No. 80NSSC19K1617, NSF Emerging Frontiers Program Award No. 1724090, and the University of Arizona Foundation Small Grants Program. BC acknowledges support from the NASA Arizona Space Grant and the Blue Marble Space Institute of Science Young Scientist Program and AKG acknowledges support from a NASA Postdoctoral Program Fellowship.

Author Contributions

Brooke M. Carruthers : Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Validation; writing-original draft; writing-review & editing. Amanda K. Garcia : Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Supervision; writing-original draft; writing-review & editing. Alex Rivier : Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Validation; writing-review & editing. Betul Kacar : Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; writing-review & editing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable–no new data generated.

Literature Cited

- Ambrosio, R., Ortiz-Marquez, J. C. F., & Curatti, L. (2017). Metabolic engineering of a diazotrophic bacterium improves ammonium release and biofertilization of plants and microalgae. Metabolic Engineering , 40, 59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.01.002.

- Arragain, S., Jimenez-Vicente, E., Scandurra, A. A., Buren, S., Rubio, L. M., & EchavarriErasun, C. (2017). Diversity and functional analysis of the FeMo-cofactor maturase NifB. Frontiers in Plant Science , 8, 1947. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01947.

- Buren, S., & Rubio, L. M. (2018). State of the art in eukaryotic nitrogenase engineering. FEMS Microbiology Letters , 365(2). doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx274.

- Burk, D., & Lineweaver, H. (1930). The influence of fixed nitrogen on Azotobacter. Journal of Bacteriology , 19(6), 389–414. doi: 10.1128/JB.19.6.389-414.1930.

- Burnett, L. C., Lunn, G., & Coico, R. (2009). Biosafety: Guidelines for working with pathogenic and infectious microorganisms. Current Protocols in Microbiology , 13(1). doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc01a01s13.

- Chavez, M., Ho, J., & Tan, C. (2017). Reproducibility of high-throughput plate-reader experiments in synthetic biology. ACS Synthetic Biology , 6(2), 375–380. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00198.

- Clementi, F. (1997). Alginate production by Azotobacter vinelandii. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology , 17(4), 327–361. doi: 10.3109/07388559709146618.

- Dingler, C., Kuhla, J., Wassink, H., & Oelze, J. (1988). Levels and activities of nitrogenase proteins in Azotobacter vinelandii grown at different dissolved oxygen concentrations. American Society for Microbiology , 170(5), 5. doi: 0021-9193/88/052148-05$02.00/0.

- Dos Santos, P. C. (2019). Genomic manipulations of the diazotroph Azotobacter vinelandii. Methods in Molecular Biology , 1876, 91–109. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8864-8_6.

- Galindo, E., Pena, C., Nunez, C., Segura, D., & Espin, G. (2007). Molecular and bioengineering strategies to improve alginate and polydydroxyalkanoate production by Azotobacter vinelandii. Microbial Cell Factories , 6, 7. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-6-7.

- Garcia, A. K., & Kacar, B. (2019). How to resurrect ancestral proteins as proxies for ancient biogeochemistry. Free Radical Biology and Medicine , 140, 260–269. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.03.033.

- Garcia, A. K., McShea, H., Kolaczkowski, B., & Kaçar, B. (2020). Reconstructing the evolutionary history of nitrogenases: Evidence for ancestral molybdenum-cofactor utilization. Geobiology , 18(3), 394–411. doi: 10.1111/gbi.12381.

- George, S. E., Costenbader, C. J., & Melton, T. (1985). Diauxic growth in Azotobacter vinelandii. Journal of Bacteriology , 164(2), 5.

- Hall, B. G., Acar, H., Nandipati, A., & Barlow, M. (2014). Growth rates made easy. Molecular Biology and Evolution , 31(1), 232–238. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst187.

- Hoffman, B. M., Lukoyanov, D., Yang, Z. Y., Dean, D. R., & Seefeldt, L. C. (2014). Mechanism of nitrogen fixation by nitrogenase: The next stage. Chemical Reviews , 114(8), 4041–4062. doi: 10.1021/cr400641×.

- Hu, Y., Fay, A. W., Lee, C. C., Wiig, J. A., & Ribbe, M. W. (2010). Dual functions of NifEN: Insights into the evolution and mechanism of nitrogenase. Dalton Transactions , 39(12). doi: 10.1039/b922555b.

- Jimenez-Vicente, E., & Dean, D. R. (2017). Keeping the nitrogen-fixation dream alive. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , 114(12), 3009–3011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701560114.

- Khdhiri, M., Piché-Choquette, S., Tremblay, J., Tringe, S. G., Constant, P., & Müller, V. (2017). The tale of a neglected energy source: Elevated hydrogen exposure affects both microbial diversity and function in soil. Applied and Environmental Microbiology , 83(11). doi: 10.1128/aem.00275-17.

- Kow, Y. W., & Burris, R. H. (1984). Purification and properties of membrane-bound hydrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii. Journal of Bacteriology , 159(2), 5. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.2.564-569.1984.

- Kurokawa, M., & Ying, B.-W. (2017). Precise, High-throughput Analysis of Bacterial Growth. Journal of Visualized Experiments , (127). doi: 10.3791/56197.

- Lee, C. C., Ribbe, M. W., & Hu, Y. (2019). Purification of nitrogenase proteins. Methods in Molecular Biology , 1876, 111–124. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8864-8_7.

- Lipman, J. G. (1903). Experiments on the transformation and fixation of nitrogen by bacteria. New Jersey State Agricultural Experiment Station , Annual Report , 23, 215–285.

- McRose, D. L., Baars, O., Morel, F. M. M., & Kraepiel, A. M. L. (2017). Siderophore production in Azotobacter vinelandii in response to Fe-, Mo- and V-limitation. Environmental Microbiology , 19(9), 3595–3605. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13857.

- Mus, F., Colman, D. R., Peters, J. W., & Boyd, E. S. (2019). Geobiological feedbacks, oxygen, and the evolution of nitrogenase. Free Radical Biology and Medicine , 140, 250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.01.050.

- Mus, F., Tseng, A., Dixon, R., & Peters, J. W. (2017). Diazotrophic growth allows Azotobacter vinelandii to overcome the deleterious effects of a glnE deletion. Applied and Environmental Microbiology , 83(13). doi: 10.1128/AEM.00808-17.

- Noar, J., Loveless, T., Navarro-Herrero, J. L., Olson, J. W., & Bruno-Barcena, J. M. (2015). Aerobic hydrogen production via nitrogenase in Azotobacter vinelandii CA6. Applied and Environmental Microbiology , 81(13), 4507–4516. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00679-15.

- Noar, J. D., & Bruno-Barcena, J. M. (2018). Azotobacter vinelandii : The source of 100 years of discoveries and many more to come. Microbiology (Reading, England) , 164(4), 421–436. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000643.

- Nosheen, A., Bano, A., Yasmin, H., Keyani, R., Habib, R., Shah, S. T. A., & Naz, R. (2016). Protein quantity and quality of safflower seed improved by NP fertilizer and rhizobacteria (Azospirillum and Azotobacter spp.). Frontiers in Plant Science , 7, doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00104.

- Olivares, J., Bedmar, E. J., & Sanjuan, J. (2013). Biological nitrogen fixation in the context of global change. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions , 26(5), 486–494. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-12-12-0293-CR.

- Page, W. J., & von Tigerstrom, M. (1979). Optimal conditions for transformation of Azotobacter vinelandii. Journal of Bacteriology , 139, 4. doi: 10.1128/jb.139.3.1058-1061.1979.

- Plunkett, M. H., Knutson, C. M., & Barney, B. M. (2020). Key factors affecting ammonium production by an Azotobacter vinelandii strain deregulated for biological nitrogen fixation. Microbial Cell Factories , 19(1), 107. doi: 10.1186/s12934-020-01362-9.

- Poole, R. K., & Hill, S. (1997). Respiratory protection of nitrogenase Activity in Azotobacter vinelandii -roles of the terminal oxidases. Bioscience Reports , 17(3), 303–317. doi: 0144-8463/97/0600-0303512.50/0.

- Setubal, J. C., dos Santos, P., Goldman, B. S., Ertesvag, H., Espin, G., Rubio, L. M., … Wood, D. (2009). Genome sequence of Azotobacter vinelandii , an obligate aerobe specialized to support diverse anaerobic metabolic processes. Journal of Bacteriology , 191(14), 4534–4545. doi: 10.1128/JB.00504-09.

- Solomon, J. B., Lee, C. C., Jasniewski, A. J., Rasekh, M. F., Ribbe, M. W., & Hu, Y. (2020). Heterologous expression and engineering of the nitrogenase cofactor biosynthesis scaffold NifEN. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) , 59(17), 6887–6893. doi: 10.1002/anie.201916598.

- Sprouffske, K., & Wagner, A. (2016). Growthcurver: An R package for obtaining interpretable metrics from microbial growth curves. BMC Bioinformatics , 17, 172. doi: 10.1186/s12859-016-1016-7.

- Wong, B. G., Mancuso, C. P., Kiriakov, S., Bashor, C. J., & Khalil, A. S. (2018). Precise, automated control of conditions for high-throughput growth of yeast and bacteria with eVOLVER. Nature Biotechnology , 36(7), 614–623. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4151.

Corrections

In this publication, an error was corrected in the A. vinelandii “UW” strain acronym, which was incorrectly defined as “University of Washington” in the Strategic Planning section. This has been replaced with the correct designation, which is “University of Wisconsin-Madison.”

Data availability statement has been added.

The current version online now includes this correction and may be considered the authoritative version of record.

Citing Literature

Number of times cited according to CrossRef: 6

- Steven J. Russell, Amanda K. Garcia, Betül Kaçar, A CRISPR interference system for engineering biological nitrogen fixation, mSystems, 10.1128/msystems.00155-24, 9 , 3, (2024).

- Derek F. Harris, Holly R. Rucker, Amanda K. Garcia, Zhi-Yong Yang, Scott D. Chang, Hannah Feinsilber, Betül Kaçar, Lance C. Seefeldt, Ancient nitrogenases are ATP dependent, mBio, 10.1128/mbio.01271-24, 15 , 7, (2024).

- Amanda K Garcia, Derek F Harris, Alex J Rivier, Brooke M Carruthers, Azul Pinochet-Barros, Lance C Seefeldt, Betül Kaçar, Nitrogenase resurrection and the evolution of a singular enzymatic mechanism, eLife, 10.7554/eLife.85003, 12 , (2023).

- Patrik Brück, Daniel Wasser, Jörg Soppa, One Advantage of Being Polyploid: Prokaryotes of Various Phylogenetic Groups Can Grow in the Absence of an Environmental Phosphate Source at the Expense of Their High Genome Copy Numbers, Microorganisms, 10.3390/microorganisms11092267, 11 , 9, (2267), (2023).

- Alex J. Rivier, Kevin S. Myers, Amanda K. Garcia, Morgan S. Sobol, Betül Kaçar, Regulatory response to a hybrid ancestral nitrogenase in Azotobacter vinelandii , Microbiology Spectrum, 10.1128/spectrum.02815-23, 11 , 5, (2023).

- Maya Venkataraman, Audrey Yñigez-Gutierrez, Valentina Infante, April MacIntyre, Paulo Ivan Fernandes-Júnior, Jean-Michel Ané, Brian Pfleger, Synthetic Biology Toolbox for Nitrogen-Fixing Soil Microbes, ACS Synthetic Biology, 10.1021/acssynbio.3c00414, 12 , 12, (3623-3634), (2023).